One morning last June in an immigration courtroom in New York City, a lawyer named Estefani Rodriguez looked as if she was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. She was a prosecuting attorney for the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE). Her job was to present immigration judges with motions to kick non-citizens out of the United States – to switch on the deportation machine.

Rodriguez is in her late 30s, with long hair and full cheeks. According to the website of the Dominican Bar Association, her parents are immigrants from the Dominican Republic. In online photos, she sports a wide smile. But on this day, as she covered one of some 60 immigration courtrooms housed in labyrinthine federal buildings in lower Manhattan, she seemed to churn with angst. Repeatedly she touched her hands to her mouth, then under her glasses, then back to her mouth, and then she rubbed and rubbed her eyes.

Rodriguez and I were calling into court via Webex, a platform for virtual appearances that resembles Zoom and is used by immigration courts nationally. Inside the physical courtroom near Broadway Street sat eight immigrants, all from Latin American countries. Some were minors, teenagers, including a 10th-grade girl the immigration judge addressed as “ma’am”. None had lawyers. The presence of two volunteer court watchers, at the ready to accompany them to the street, suggested that masked ICE agents lurked in the hallway. When the judge called a 10-minute break for everyone to use the bathroom, the immigrants stayed glued to their seats.

Some had crossed into the country from Mexico many months earlier without prior approval from US immigration authorities, then applied for asylum. Though traditionally considered legal under international and US immigration law, the Trump administration had announced that most people who entered this way in the past two years could no longer get asylum and could be arrested in courthouses. The move shocked, confused and angered advocates for immigrants’ rights. It gave the agents license to grab even more people, and to send them to detention and deportation. By late June, when I saw Rodriguez, this was happening routinely.

The judge asked Rodriguez if two of the immigrants who had made the Mexico-to-US crossing were now banned from further pursuing their asylum claims. “It appears that they are,” Rodriguez said in a flat voice.

In August, Rodriguez quit. “After nearly nine years in the federal government, I resigned from my position at DHS,” she wrote on her LinkedIn page, adding that her decision had been “difficult but necessary”. Soon, she started reposting materials that suggested a reason. One such post, from the National Immigration Project, offered a training for lawyers on “current trends and strategies to confront ICE’s expanding reach and unlawful practices”.

Nationwide, ICE employs about 1,700 attorneys. Their work is vital to the Trump administration’s goal of deporting 1 million people a year. And in courtrooms nationally, that work is intensifying. According to a Mobile Pathways, a California non-profit that publishes immigration data, in 2025 asylum was granted in only 11% of cases – a decline compared with the Biden years – while 43% of applicants were denied asylum. Under Biden, 14% of asylum applications had been abandoned, leading to automatic orders of deportation. But in 2025 a third were, probably due to immigrants not daring to attend their hearings as courthouse arrests jumped. In July I saw a Spanish speaker run from the courthouse and attempt to attend his hearing from the safety of Webex on his mobile phone. “I’m scared!” he told the judge. An ICE agent in a cherry-red balaclava was visible on the screen, lurking by the courtroom door. When the man did not return to the courtroom as ordered, the judge threw out his asylum case as “abandoned”.

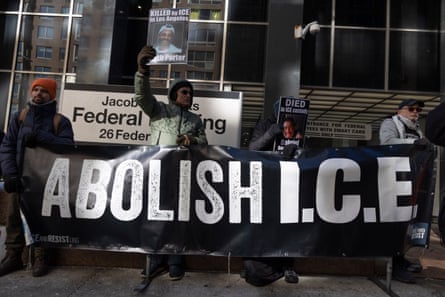

While the media are filled with coverage about fired immigration judges and the ICE agents who stalk the system, ICE attorneys go largely unnoticed.

From June 2025 into early 2026, I attended hearings with more than 40 ICE attorneys in Manhattan, watching as they helped turn the immigration court system into an increasingly perverse parody of due process. The strategies they have used to curtail asylum since the beginning of Donald Trump’s second term – some of which I saw play out in courtrooms – are newly fashioned and tawdry, according to court watchers, a former ICE attorney, and fired immigration judges.

Like Rodriguez, not all of the attorneys looked happy with the work. Last summer an ICE lawyer in Washington DC, Adam Boyd, quit, telling the Atlantic he had made “a moral decision” after watching ICE lawyering turn into “a contest of how many deportations could be reported to Stephen Miller by December”.

As summer turned to fall and winter, I identified four New York City attorneys who have left ICE since Trump’s inauguration, including Rodriguez. However, repeated attempts to contact them were met with silence.

They are staying mum, said a retired civil attorney who volunteers as a New York City court watcher, because lawyers should never speak negatively about their former clients – even if the client is the federal government. George Pappas, a former immigration judge, suggested a different reason: “They’re scared shitless of what the press will say about them.” When they look for other jobs, he said, “they’re afraid they’re going to get blacklisted”.

Democrats, children of immigrants and patriots

US immigration courts are not courts as most Americans understand the term. They are not part of the judiciary, instead housed in the Department of Justice, which is controlled by the executive. The court system’s judges are meant to act independently but are hired – and fired – by the justice department. Its prosecuting attorneys work for ICE, also part of the executive. Further, unlike in the criminal justice system, people charged for violating immigration law have no right to a no-cost lawyer, even when they are detained. Critics including the American Civil Liberties Union have long denounced immigration adjudications as “kangaroo courts”.

Still, some ICE lawyers saw humanitarian elements in the work.

When a person was detained by ICE or border patrol agents and charged with being in the US without authorization, they could claim to have a reason to remain – that they were seeking asylum, for instance. This claim landed them in the immigration court system, facing off against an ICE lawyer whose job it was to find reasons to deport them. Or, as was sometimes the case during the Biden administration, reasons for letting them stay. For those immigrants who were not national security or public safety threats, or had years of residence in the US or US-born children, ICE lawyers were allowed, even encouraged, to make exceptions on a case-by-case basis. The government reasoned that prosecutorial discretion cleared crowded court dockets and opened up space in detention centers for immigrants it considered dangerous.

An immigration judge who was fired after Trump’s second inauguration, and who asked for anonymity, recalled how, during the Biden administration, ICE lawyers frequently dispensed with rebuttals and closing arguments and would instead “defer to the court” or “rest on the record”, which tended to encourage rulings more sympathetic to immigrants’ asylum claims.

All of this changed when Trump’s second term began and ICE lawyers were pressured to not agree to any decision by an immigration judge considered adverse to the government’s intent to deport.

George Pappas served as an immigration judge in Massachusetts courts from 2023 to last summer, when he, too, was fired without cause. Under Trump, about 100 of 735 judges nationwide have been fired, even some who had low asylum grant rates. The justice department is now advertising for replacements, and making clear that conscientious adjudication of asylum claims is no longer the point. “Help write the next chapter of America,” the department’s online recruiting graphic reads. “Apply today to become a deportation judge.”

“Asylum is dead now,” Pappas said.

So far, no news has emerged about ICE lawyers being fired.

On social media profiles, some New York City ICE lawyers omit their occupation and conceal their full names. Cosette Shachnow uses only “S” on her LinkedIn page, and there is no mention she works for ICE. This past summer, in a Manhattan court, an immigration judge refused to utter Shachnow’s name on the record. When a defense attorney protested against this, saying it was a due process violation, the judge said she needed to protect Shachnow’s safety. She did not specify what the safety concern was.

ICE does not publicly release names of ICE lawyers. But even judges who avoid using them often utter them once or twice as hearings grind on. Of the 44 lawyers I saw working in Manhattan, whose names I confirmed via the official state attorney site, I found public emails for 23 of them; none but one responded to interview requests. But with everyone’s full name I was able to look up information about them in databases, social media profiles and online publications. Something of a character profile emerged.

The group is split about equally between white people and people of color from a range of ethnic backgrounds. According to New York and New Jersey voter registration records, 37 are on the rolls, and over half of these – 21 – are Democrats. Three attorneys, all white, are registered Republicans; the rest did not specify a political party. Many have backgrounds as assistant prosecutors in district attorneys’ offices. Many have also done defense work, including with non-profits that advance immigrant and human rights.

One such lawyer is 34-year-old Amit Noor. His family is from Bangladesh, and as a student at Yeshiva University’s Cardozo law school, he joined a human rights and atrocity prevention clinic that won asylum for a Chinese woman who had been jailed in China for engaging with Falun Gong, a spiritual practice banned by the Chinese communist party. As an undergraduate, Noor wrote admiringly in a student newspaper about an ageing immigration attorney’s tireless efforts to help immigrants gain asylum. On the morning in late June when I saw him working, he remained silent until an immigrant who lived in Queens and had no lawyer appeared for his hearing on Webex. Noor perked up. “Why is he not here in person?” he asked the judge.

Online, Noor and many of the other ICE attorneys seem like typical, upwardly mobile New York City professionals. One loves exploring interesting dining spots in Brooklyn, and she was accepted as a member in the Park Slope food co-op. Another does jiujitsu. One posts on Facebook about romantic weekends with his partner in the Hudson valley. Most have attended law schools in the New York City area including Columbia, Yeshiva, NYU and Fordham.

In courthouses, they seldom get noticed. The women dress in understated suit jackets, pencil skirts and little heels; the men sport menswear analogs. Stepping into the chaos in the halls, they are tasteful ghosts. Inside courtrooms they speak in deferential, almost old-fashioned voices – “Yes, your honor. No, your honor” – as they make their cases for deportation.

In July I watched on Webex as ICE attorney Ira Okyne, a 44-year-old Brooklynite, told the judge that the government wished to “dismiss” the cases of several immigrants in the room. To justify each dismissal, he offered the same boilerplate motion: “Circumstances have changed,” and continuing the case was no longer “in the government’s interest”.

To immigrants, “dismissal” may have sounded wonderful, as though the government was no longer interested in deporting them. In fact, the exact opposite was true. Getting a dismissal generally meant that by the time the immigrants exited the courtroom, they had lost their status as people in the US who had some kind of paperwork to be here. This made them subject to immediate arrest by waiting agents. According to the New York Times, in May the justice department had distributed a memo instructing ICE attorneys to work with ICE agents by passing them immigrants’ exact court dates and locations.

One immigrant whose case Okyne was handling was a Black man who spoke French. Hearing the motion, he became distraught. “Please!” he begged the judge through an interpreter, as Okyne watched, impassive. “Please, don’t dismiss my case!” Terrified of what awaited him outside the courtroom, the man resisted leaving. He was ordered to, anyway. Later, I learned that he had been seized in the hallway by masked ICE agents.

Okyne was the only ICE attorney to respond to my request for an interview, directing me to ICE’s office of public affairs. ICE did not respond to requests for comment.

Veronica Cardenas used to be an ICE prosecutor in New York City, but she quit in 2023. Her parents had come to the US from Colombia and Peru before she was born. Only years later did she learn that her mother was undocumented when she first arrived.

Cardenas was recruited to ICE work via a justice department honors program for law students, which hires them even before they pass their bar exam. She said that when she started working for ICE, she thought she was protecting the country by deporting dangerous criminals. There were also times when she declined to argue against asylum cases. But the denials piled up. “I saw so many immigrants who were just like my mother.” She tried to apply for other jobs, but she did not get responses. “Someone said: ‘No one wants to hire you because you work for ICE.’” She now has a solo immigration defense practice in New Jersey.

Since Trump began his second term, Cardenas has counseled ICE attorneys who have told her they want to leave, but few have gone through with resignations. Like her, they come from immigrant families. But, she said, many feel that they have no choice but to remain with ICE. “A lot are new lawyers,” she said. “They have mortgages. They’re helping their own parents financially. They’ve got student loans.”

ICE attorneys in New York City earn more than $100,000 a year after they begin working. They enjoy generous health and vacation benefits typical of federal government jobs, as well as retirement pensions. They can have their student loans forgiven. Some aspire to more prestigious prosecutor positions in the justice department; they see ICE lawyering as their gateway. Some want to be immigration judges.

Sociologist Dylan Farrell-Bryan, formerly of the University of Pennsylvania, interviewed dozens of ICE attorneys during Trump’s first term, when his administration began introducing anti-immigration procedural changes into the courts, and into Biden’s tenure. She published her findings in 2024. White, male attorneys frequently told her that they did ICE lawyering out of a sense of patriotism and desire to keep America safe from criminals and asylum fraudsters. Female lawyers, however, described deportation litigation as a neutral process that they followed as conscientious civil servants. “Sometimes the law doesn’t let us do what the public would view as the right thing,” said one. “You go home. You sleep at night,” said someone else. Another said that her job was to “do what I’m told”.

Farrell-Bryant called these rationales “an unthinking internalization of duty”, and she contextualized them through the work of Hannah Arendt. A German Jewish philosopher and Holocaust refugee, Arendt studied the behavior of bureaucrats in Nazi Germany as they carried out Hitler’s genocide. She coined the concept “banality of evil”.

The attorneys who quit

In recent months, the strategy of dismissals seemed to give way to something unheard of in immigration courts. On orders from the justice department, ICE lawyers are, as a matter of course, making oral motions for what in immigration-law language is called “pretermission”. The term means to summarily cancel an asylum application before a final hearing, usually because the paperwork purportedly lacks enough information to justify granting the petition. Immigrants used to have the due process right to come back to court with a more detailed application, and to personally stand before the judge and defend it. Now, not only are many judges cancelling asylum cases after ICE lawyers propose pretermission, but ICE lawyers are now moving to send pretermitted immigrants to foreign countries they have never been to.

In April 2025, amid thousands of cases in immigration courts nationwide, ICE lawyers made only 133 pretermission motions. By November the monthly tally had increased 40-fold, then more than doubled in the next month. Few pretermissions so far have been enacted; their legality is being challenged in various federal courts. Nevertheless by December they had crashed over Manhattan’s courtrooms like a tsunami.

In January I watched an ICE lawyer move for pretermission of a Mauritanian man to Uganda. The judge, F James Loprest, gave the man’s attorney a month to submit a response. Meanwhile, he suggested that the Mauritanian simply quit the US before the pretermission decision came down by exercising an option called “voluntary departure”. The term means leaving the US on one’s own and abandoning an asylum claim. “We’re always open to that,” Loprest told the man.

Amid the roil of pretermission motions, I found the public resignation post of an ICE attorney in New York City – to my knowledge, the fourth who had quit. “I stand with my people,” Andy Viera-Rivera wrote in December on his LinkedIn page. “My Latinos. Mi gente. Their stories, their sacrifices, their resilience, and their dreams of safety, dignity and belonging are not abstract to me. They are my family. They are my history.” On the site for his new immigration defense law firm he writes that he left ICE because “it was time to take a stand”.

Rodriguez, the attorney who was so visibly suffering when I saw her in court, now works at the law school of New Jersey’s Seton Hall University. In a 180-degree occupational turn, she helps students there do pro-bono defense work for immigrants facing detention and deportation.

A few weeks ago, she reposted an invitation to immigration legal advocates in New York for a group therapy to process emotional trauma wreaked by working under Trump’s immigration crackdown. The sessions would be led by a psychotherapist and a “death doula” who helps people process grief. Of the fired judges, former ICE lawyers and exhausted immigration defense attorneys I spoke with, no one could explain why more ICE lawyers have not quit the chaos and cruelty of the immigration courts, nor publicly denounced what they must do there to keep their jobs. No one could say whether the courts would get better soon. Or worse.

Rodriguez herself has written that as a former prosecutor of immigrants for ICE, she still struggles with “how to be someone’s champion. To not see the holes in the case, but to try to look at the best way to present the case. Most importantly, how to care deeply about the outcome again.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 hours ago

3 hours ago

Comments