On the evening of May 21, 1796, Ona Judge made the daring decision to free herself.

Considering the prominence of her owner, the laws of the time and the dangerous trek to New Hampshire, a place where she could discreetly live freely, the act carried remarkable risk. Nevertheless, she slipped out of the President’s House undetected while the first family dined.

The house, then located at the intersection of 6th and Market streets in Philadelphia, served as the first executive mansion. It stood mere feet from Independence Hall, where the nation adopted its lofty language regarding freedom.

Years later, Judge described her narrow escape to Rev. Benjamin Chase in an interview for the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. Judge told Chase, “I had friends among the colored people of Philadelphia, had my things carried there beforehand, and left Washington’s house while they were eating dinner.”

Prior to her escape, Judge served as a chambermaid in the President’s House. She spent years tending to Martha Washington’s every need: bathing and dressing her, grooming her hair, laundering her clothes, organizing her personal belongings, and even periodically caring for her children and grandchildren.

Being a chambermaid also included grueling daily tasks such as maintaining fires, emptying chamber pots and scrubbing floors.

Even though she engaged in this arduous labor as property of the Washingtons, living in Philadelphia provided Judge a glimpse of what freedom could eventually look like for her. Historians estimate that 5% to 9% of the city’s population at the time were free Black people. Prior to her escape, Judge befriended several of them.

In the spring of 1796, the Washingtons prepared to return to Virginia to resume private life. President Washington issued his farewell address in the fall of 1796, but he told family and close confidants of his plans earlier in the year.

During that time, Martha Washington made arrangements for their pending return to Mount Vernon. Her plans included bequeathing Ona Judge to her granddaughter, Elizabeth Parke Custis, as a wedding gift. Upon learning this, Judge made plans of her own.

In her interview with Chase she explained, “Whilst they were packing up to go to Virginia, I was packing to go, I didn’t know where; for I knew that if I went back to Virginia, I should never get my liberty.”

As a civil rights lawyer and professor in the Africology and African American Studies department at Temple University in Philadelphia, I study the intersection of race, racism and the law in the United States. I believe Judge’s story is vital to the telling of America’s history.

Dismantling history

Erica Armstrong Dunbar, a professor of African American Studies at Emory University, tells Judge’s fascinating story in her book “Never Caught: The Washingtons’ Relentless Pursuit of their Runaway Slave Ona Judge.”

Before January 2026, those who wished to learn about Judge could literally stand on the same walkway in Philadelphia where Judge once stood when she chose to flee. Several footprints, shaped like a woman’s shoes and embedded into the pathway outside of where the President’s House once stood, memorialize the beginning of Judge’s journey. These footprints composed part of an exhibit examining the paradox between slavery, freedom and the nation’s founding.

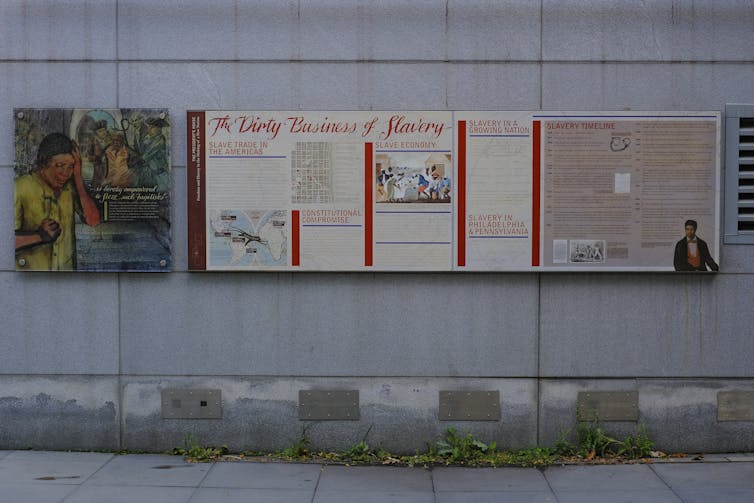

The exhibit, “Freedom and Slavery in the Making of a New Nation,” also included 34 explanatory panels bolted onto brick walls along that sidewalk. They provided biographical details about the nine people the Washingtons owned while living in the presidential mansion. The exhibit presented the sobering reality that our nation’s first president enslaved people while he held the nation’s highest office.

This changed in late January when the National Park Service dismantled the slavery exhibit at Philadelphia Independence National Historic Park. The removal sparked intense, immediate outrage from people across the country dismayed by the attempt to suppress unfavorable aspects of American history.

Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker responded swiftly. “Let me affirm, for the residents of the city of Philadelphia, that there is a cooperative agreement between the city and the federal government that dates back to 2006,” she said in a public statement. “That agreement requires parties to meet and confer if there are to be any changes made to an exhibit.”

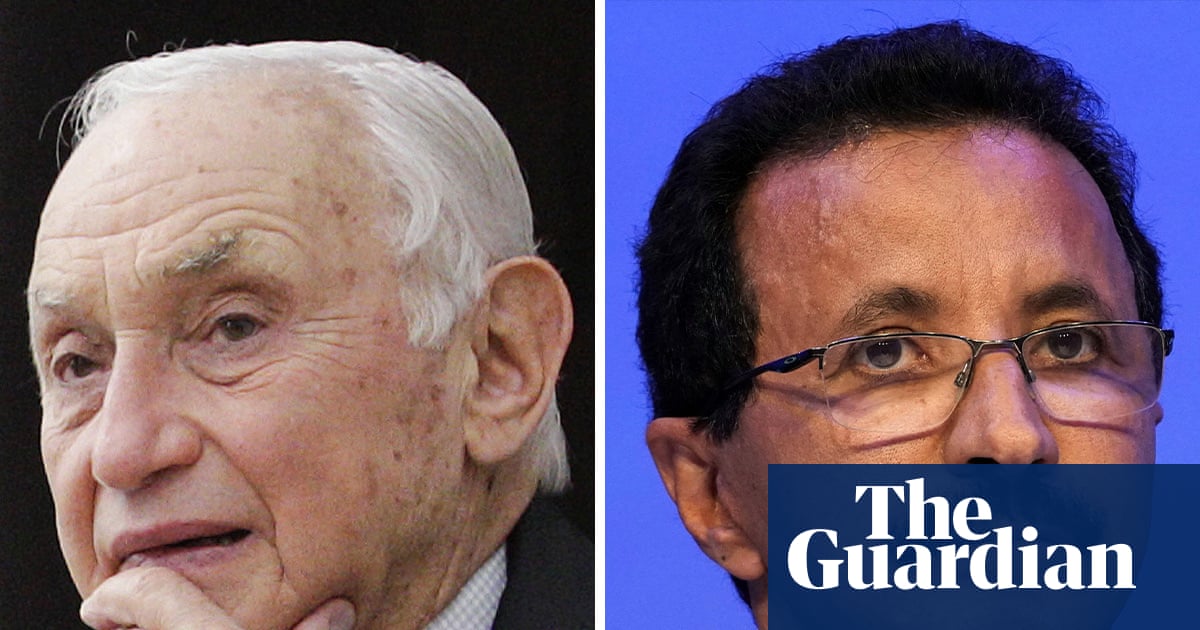

The city of Philadelphia later sued Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and National Park Service acting Director Jessica Bowron. Pennsylvania subsequently filed an amicus brief in support of the city’s lawsuit.

After an inspection of the exhibit’s panels, U.S. District Judge Cynthia Rufe, who is overseeing the case, ruled that the government must mitigate any potential damage to them while they are stored.

Civil rights activist and Philadelphia-based attorney Michael Coard recently had an opportunity to visit and examine the exhibits in storage. Coard has led the fight to create and preserve the exhibit and now is at the center of the fight to restore it.

Limiting discussion of race

While the court deliberates the future of the exhibits, critics continue to raise key concerns regarding the exhibit’s removal. Many argue the National Park Service’s dismantling of the exhibit is an attempt to “whitewash history” and erase stories like Ona Judge’s.

This is particularly the case considering the Trump administration has restored and reinstalled two Confederate monuments of Albert Pike in Washington, D.C., and Arlington National Cemetery, while removing the slavery exhibit in Philadelphia.

Moreover, during the first week of his second term, Trump signed multiple executive orders to eliminate diversity, equity and inclusion policies.

Similarly, during the first Trump administration, the federal government engaged in various efforts to counterbalance the 1619 Project, a project spearheaded by Pulitzer-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones that discussed the 400th anniversary of slavery’s beginnings in America. The 1619 Project spawned yearslong backlash. This included the 1776 Commission, created during the first Trump administration, which tried to discredit the conclusions of the 1619 project.

It is all part of a broader pattern across the country to limit how public institutions broach topics pertaining to race and racism.

This pattern has intensified as the United States prepares to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the framers signing the Declaration of Independence. As the nation celebrates its history, it must decide how much of it to explore.

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, or sign up for our Philadelphia newsletter on Substack.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 hours ago

2 hours ago

Comments