As the United States faces increasing incidents of book banning and threats of governmental intervention – as seen in the temporary suspension of TV host Jimmy Kimmel – the common reflex for many who want to safeguard free expression is to turn to the First Amendment and its free speech protections.

Yet, the First Amendment has not always been potent enough to protect the right to speak. The Cold War presented one such moment in American history, when the freedom of political expression collided with paranoia over communist infiltration.

In 1947, the House Un-American Activities Committee subpoenaed 10 screenwriters and directors to testify about their union membership and alleged communist associations. Labeled the Hollywood Ten, the defiant witnesses – Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott and Dalton Trumbo – refused to answer questions on First Amendment grounds. During his dramatic testimony, Lawson proclaimed his intent “to fight for the Bill of Rights,” which he argued the committee “was trying to destroy.”

They were all cited for contempt of Congress. Eight were sentenced to a year in federal prison, and two received six-month terms. Upon their release, they faced blacklisting in the industry. Some, like writer Dalton Trumbo, temporarily left the country.

As a researcher focused on the cultural cold war, I have examined the role the First Amendment played in the anti-communist hearings during the 1940s and ’50s.

The conviction and incarceration of the Hollywood Ten left a chilling effect on subsequent witnesses called to appear before congressional committees. It also established a period of repression historians now refer to as the Second Red Scare.

Although the freedom of speech is enshrined in the Constitution and prized by Americans, the story of the Second Red Scare shows that this freedom is even more fragile than it may now seem.

The Fifth Amendment communists

After the 1947 hearings, the term “unfriendly” became a label applied by the House Un-American Activities Committee and the press to the Hollywood Ten and any witnesses who refused to cooperate with the committee. These witnesses, who wanted to avoid the fate of the Hollywood Ten, began to shift away from the First Amendment as a legal strategy.

They chose instead to plead the Fifth Amendment, which grants people the right to protect themselves from self-incrimination. Many prominent artists during the 1950s, including playwright Lillian Hellman and singer and activist Paul Robeson, opted to invoke the Fifth when called before the committee and asked about their political affiliations.

The Fifth Amendment shielded hundreds of “unfriendly” witnesses from imprisonment, including artists, teachers and federal workers. However, it did not save them from job loss and blacklisting.

While they could avoid contempt citations by pleading the Fifth, they could not erase the stain of perceived guilt. This legal approach became so widespread that U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy, the country’s leading anti-communist crusader, disparaged these witnesses as “Fifth Amendment Communists” and boasted of purging their ranks from the federal government.

From Fifth back to First

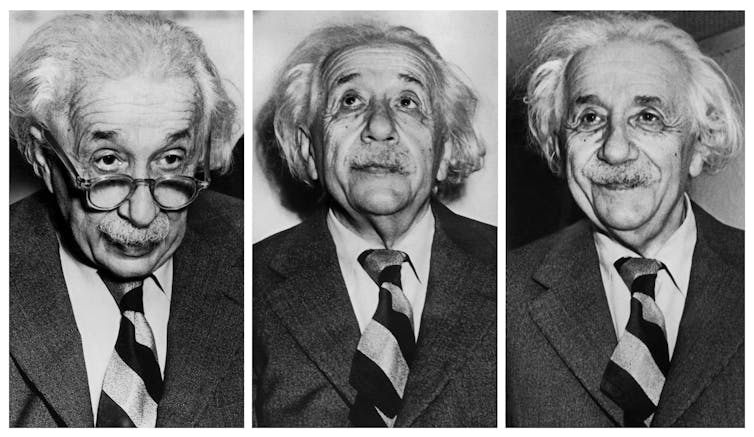

In 1953, the physicist Albert Einstein became instrumental in revitalizing the force of the First Amendment as a rhetorical and legal tactic in the congressional hearings. Having fled Germany after the Nazis came to power, Einstein took a position at Princeton in 1933 and became an important voice in American politics.

Einstein’s philosophical battle against McCarthyism began with a letter to a Brooklyn high school teacher named William Frauenglass.

In April of that year, Frauenglass was subpoenaed to appear before the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, “the Senate counterpart” of the House Un-American Activities Committee, to testify about his involvement in an intercultural education seminar. After the hearing, in which Frauenglass declined to speak about his political affiliations, he risked potential termination from his position and wrote to Einstein seeking support.

In his response, Einstein urged Frauenglass and all intellectuals to enact a “revolutionary” form of complete “noncooperation” with the committee.

While Einstein advised noncompliance, he also acknowledged the potential risk: “Every intellectual who is called before one of the committees ought to refuse to testify, i.e., he must be prepared for jail and economic ruin, in short, for the sacrifice of his personal welfare in the interest of the cultural welfare of his country.”

Frauenglass shared his story with the press, and Einstein’s letter was published in full in The New York Times on June 12, 1953. It was also quoted in local papers around the country.

One week later, Frauenglass was fired from his job.

After learning about Einstein’s public position, McCarthy labeled the Nobel laureate “an enemy of America.” That didn’t stop Einstein’s campaign for freedom of expression. He continued to encourage witnesses to rely on the First Amendment.

When the engineer Albert Shadowitz received a subpoena in 1953 to appear before McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, to answer questions about alleged ties to the Communist Party, he traveled to Einstein’s home to seek out the physicist’s advice. After consulting with Einstein, Shadowitz opted for the First Amendment over the Fifth Amendment.

On Dec. 16, 1953, Shadowitz informed the committee that he had received counsel from Einstein. He then voiced his opposition to the hearing on the grounds of the First Amendment: “I will refuse to answer any question which invades my rights to think as I please or which violates my guarantees of free speech and association.”

He was cited for contempt in August 1954 and indicted that November, facing a potential year in prison and US$1,000 fine. As an indicator of McCarthy’s diminishing power, the charge was thrown out in July 1955 by a federal judge.

The triumph of dissent

Well-known public figures also began to turn away from the Fifth Amendment as a legal tactic and to draw on the First Amendment.

In August 1955, when the folk musician Pete Seeger testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee, he voiced his rejection of the Fifth Amendment defense during the hearing. Seeger asserted that he wanted to use his testimony to call into question the nature of the inquiry altogether.

Pleading the protection of the First Amendment, Seeger refused “to answer any questions” related to his “political beliefs” and instead interrogated the committee’s right to ask such questions “under such compulsion as this.”

When the playwright Arthur Miller was subpoenaed by the committee in 1956, he also refused to invoke the Fifth. Both were cited for contempt. Seeger was sentenced to a year in prison. Miller was given the option to pay a $500 dollar fine or spend 30 days in jail.

As Seeger and Miller fought their appeals in court, McCarthy’s popularity continued to wane, and public sentiment began to shift.

Prompted by Einstein, the noncompliant witnesses in the 1950s reshaped the public discussion, refocusing the conversation on the importance of freedom of expression rather than the fears of imagined communist infiltration.

Although the First Amendment failed to keep the Hollywood Ten out of prison, it ultimately prevailed. Unlike the Hollywood Ten, both Miller and Seeger won their appeals. Miller spent no time in prison and Seeger only one day in jail. Miller’s conviction was reversed in 1958, Seeger’s in 1962. The Second Red Scare was over.

As the Second Red Scare shows, when free speech is under attack, strategic compliance may be useful for individuals. However, bold and courageous acts of dissent are critical for protecting First Amendment rights for everyone.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 hours ago

3 hours ago

Comments