During Donald Trump’s first term, the US’s corporate titans were prepared to literally turn their backs on the president when they disagreed with them. Weeks of growing national anger over deadly immigration crackdowns in the US have highlighted how much has changed.

Publicly, the US’s top CEOs have stayed – mostly – quiet during Trump’s second term, even as his administration has undermined free trade policies, cracked down on the immigration that many businesses relied on, and attacked the Federal Reserve – a pillar of the US’s financial hegemony.

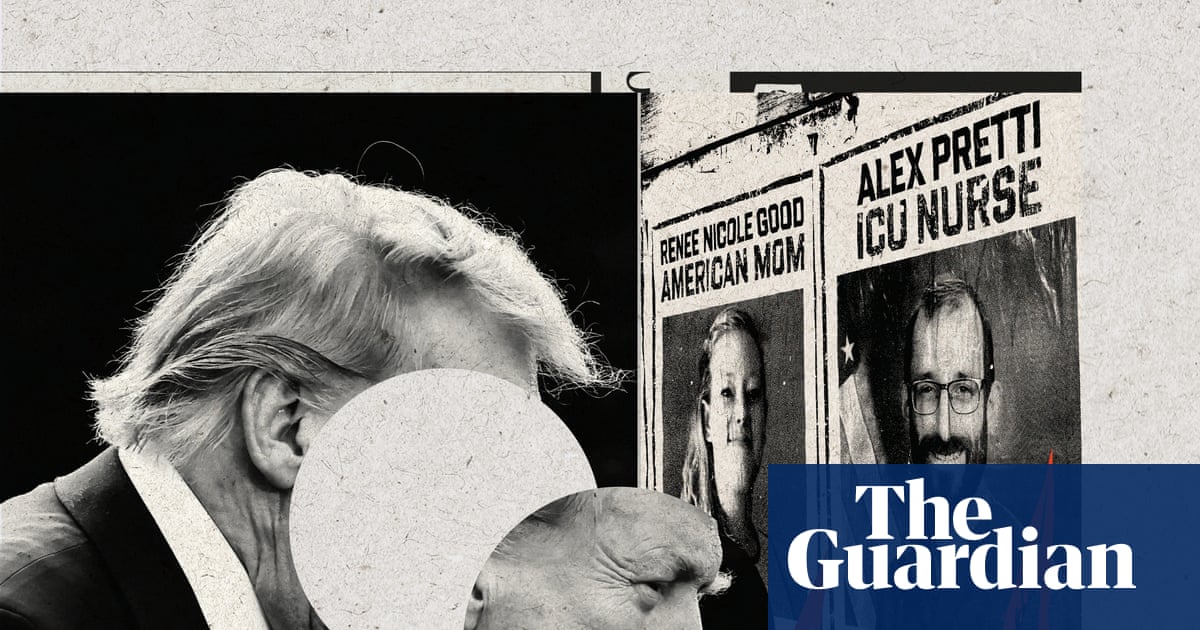

But the administration’s brutal handling of its immigration raids in Minnesota and the killing of Alex Pretti in Minneapolis have tested the reticence of the corporate class to its limits, highlighting their lack of leadership amid growing public anger.

A day after federal agents pinned down and shot protester Pretti, 37, to death on 24 January, a group of 60 CEOs of Minnesota-based companies including Target, Best Buy, 3M and General Mills released a group statement calling for the “immediate de-escalation of tension” and for law enforcement agencies “to work together to find real solutions”.

“The recent challenges facing our state have created widespread disruption and tragic loss of life,” the statement read, which came after Renee Good, an unarmed woman, was also killed by federal agents in Minneapolis.

A separate statement from Michael Fiddelke, incoming CEO of Target, which is headquartered in Minneapolis, also did not mention Pretti, Good or the actions of federal law enforcement. “What’s happening affects us not just as a company, but as people, as neighbors, friends and family members within Target,” Fiddelke said.

The statements ended up producing a backlash against what many saw as a response too soft given the circumstances. People pointed out that neither Pretti nor Good were mentioned by name. At least eight people have either been killed by federal agents or died while in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody in 2026 so far.

The pressure to say something is mounting, but the US’s CEOs have so far failed to rise to the moment. Apple CEO Tim Cook, who on Saturday attended a VIP screening of the Melania Trump documentary at the White House, said he was “heartbroken by the events in Minneapolis” and that it was “time for de-escalation” in an internal message to Apple’s workforce. Apple’s workers are reportedly “livid” about Cook’s attendance at the screening.

“De-escalation” has become the go-to safe word for US CEOs, according to an analysis by the Wall Street Journal. In the meantime, protesters are organizing strikes and business boycotts.

Historically, American corporations have been careful to stay out of politics as best as they can, framing themselves as friendly and neutral to all. But as American politics have become more divisive over the last decade, corporations have found themselves caught in a tightening bind. Whether they respond or not, there will be consequences.

“There’s no good decision. That’s the kind of era that we’re in right now,” said Alison Taylor, a clinical associate professor at New York University’s Stern business school.

In the last few years, corporations have gone from fearing liberal consumer backlash to anxieties about conservative boycotts. Now, many companies’ biggest concern is being targeted by the Trump administration.

“The risks are really not theoretical – they’re real,” Taylor said. “The administration is using a mix of public shaming and litigation. Are you going to be exempt from tariffs, or is your industry going to be subject to tariffs? Are we going to favor your competitors? There’s a lot of economic levers the administration is using.”

Trump has made clear he’s unafraid to use his vast executive powers against his enemies or anyone he deems to be too “woke”.

Many corporate executives have done their best to maintain friendly ties. Trump made sure the most powerful tech CEOs, including Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg and Sam Altman, were in attendance at his inauguration last year. Paramount and Disney, owners of CBS News and ABC News, respectively, paid out millions of dollars to settle defamation lawsuits, and Meta paid $25m to the president over its decision to deplatform Trump after the January 6 insurrection. Amazon recently paid $30m to Melania Trump to acquire the documentary about her life.

“The government’s voice has become hugely amplified on a state and federal level to the point where, when Paramount and Netflix are talking about acquiring Warner Bros, the headlines are: ‘Does Netflix have a White House problem?’,” said Elizabeth Doty, executive director of Third Side Strategies, a thinktank and advisory firm that helps companies with public affairs. Doty said there’s been a high-level shift toward “allegiances and loyalties, rather than rules and entrepreneurial competition” in Trump’s second term.

The responses from corporate America today are dramatically different from in the 2010s and early 2020s, an era when companies were trying to align themselves with liberal causes like Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ+ rights and climate activism.

When Donald Trump said there were “some very fine people on both sides” in the aftermath of the Charlottesville white supremacist rally in 2017, CEOs started to publicly distance themselves from the president. As climate activism became more prominent, companies promised to pivot to environmental, social and governance (ESG) investments.

After George Floyd’s murder, also in Minneapolis, social media was flooded with corporations making statements in support of Black Lives Matter. JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon was photographed taking the knee in front of a bank vault. Companies flowed right along the tide of the racial reckoning, promising billions of dollars of investment into ensuring diversity and inclusion.

The corporate backlash against the January 6 insurrection was also swift and pronounced, with some companies announcing they would temporarily halt political donations and spending after the riot.

But even before Trump was reelected, the tides were starting to turn. The conservative movement against “woke” politics, including state laws banning diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives, started to take hold. Conservative boycotts on social media fueled backlashes against products and companies like Bud Light and Target. Companies quietly dropped the diversity teams they formed after George Floyd.

And when Trump started his second term, he reentered the White House with a vengeance that has shaken many corporations.

“Corporations or brands felt like they were trapped between the left wing and the right wing,” Taylor said. “The problem then was perceived to be polarization. Today, we’ve still got polarization, but it’s more about retaliation from the regime … and how we manage backlash from the government, versus backlash from the general public.”

Last week, Trump, through his personal lawyer, filed a lawsuit against JPMorgan and Dimon for “debanking” him after the US Capitol insurrection. The lawsuit came quickly after Dimon spoke up in defense of US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell, whom Trump’s justice department put under criminal investigation. Dimon said that chipping away at Fed independence “is not a good idea”, to which Trump quickly responded: “It’s fine what I’m doing.”

But the calculus for speaking out against issues like what’s happening in Minnesota isn’t just mitigating “woke” consumers and employees and a threatening federal government, Doty said. Even more is at risk when key institutions and principles are kicked away without consequences or criticism.

“Due process, rule of law, civic spaces and adherence to the constitution – all of those are essential to the environment [corporations] need,” Doty said. “The bigger choice right now is, are we going to be an economy based on loyalties and allegiances, or [one] based on institutions?”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 hours ago

3 hours ago

Comments