Throughout Bad Bunny’s mesmerizing performance during the Super Bowl, the word “America” kept expanding, like an accordion, stretching out to embrace people of all nationalities. “Together we are all America,” his football read, and he obviously meant it, in the largest, most hemispheric sense. Near the end, after shouting “God bless America” (his only words in English), Bad Bunny ran through a long list of countries in the western hemisphere.

That inclusiveness enraged Donald Trump, who erupted on social media, and tried to take the word back, declaring the half-time show “an affront to the greatness of America”. By which, of course, he meant the United States.

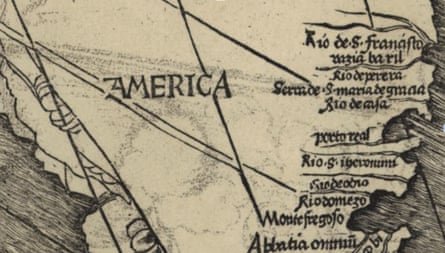

It was refreshing to encounter this greater America – or more accurately, to welcome it back. It has always been there, since the word “America” first appeared, hovering over Brazil in a 1507 map.

Ever since he was inaugurated, Trump has acted as if he owns the word “America”. Throughout his second inaugural address, he used it as a synonym for the US. (“America will soon be greater, stronger, and far more exceptional than ever before.”) His “America first” foreign policy assumes the right to take possession of any part of the hemisphere he wants, whether it’s the oilfields of Venezuela or the frozen tundra of Greenland.

This view is perhaps best understood through his repackaging of the Monroe doctrine, which Trump has increasingly invoked as a “big deal” to justify his desire to dominate the hemisphere. In his view, the doctrine appears to be a mantra for an amped-up foreign policy that may soon extend to other nations on Bad Bunny’s list, including Cuba, Colombia and Panama.

So why is a 203-year-old footnote from American history, first articulated in James Monroe’s 1823 message to Congress, rattling around the president’s head?

While Trump has not paused to define what he now calls the “Donroe doctrine”, it appears to be synonymous with a “Trump Corollary”, recently announced in the 2025 National Security Strategy, that would update the Monroe doctrine by alerting all “non-Hemispheric competitors” – presumably China, Russia and Iran – that they will not be able to position forces or own “strategically vital assets” in our region. (That will come as news to the Chinese, who have spent years and billions of dollars building an enormous deep-water port in Chancay, Peru, announced in 2019. They will not be leaving anytime soon.)

After introducing the Donroe doctrine during a rambling news conference after the seizure of Nicolás Maduro, Trump promised that “American dominance in the western hemisphere will never be questioned again”. A month earlier, the White House issued a celebratory announcement of the 203rd anniversary of the Monroe doctrine – not an anniversary noted by any previous administration, including Monroe’s. In his message, Trump announced: “I am proudly reasserting this time-honored policy.”

These announcements were followed in short order by the Maduro raid, and the threat to annex Greenland, which revealed an administration suddenly anxious over the foreign domination of this hemisphere (despite no evidence, in the Greenland case, of Russian or Chinese naval activity).

Except that Trump has read history incorrectly. Trump sees the Monroe doctrine as a military threat, a way to bully other superpowers out of the western hemisphere and plunder the Americas for any resources the US might want. But in its original formation, the Monroe doctrine was a statement of pan-American solidarity – much closer to Bad Bunny’s than Donald Trump’s.

Self-determination, not dominance

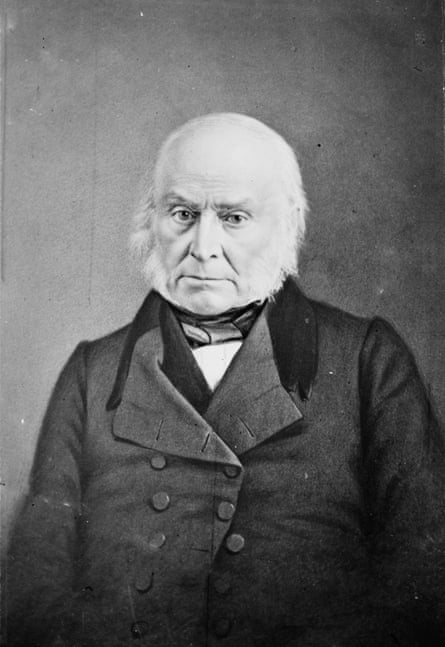

The original doctrine, as written out by a visionary secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, is irreconcilable with the Trump administration’s interpretation of it. It was a plea to give the nations of South America a chance to develop democratic institutions of their own, away from the great powers of Europe. It was more about self-determination than dominance, and more about allies than Trump’s go-it-alone attitude. Specifically, it pulled together the United States and the United Kingdom, who only recently had been at war with each other. In its way, the Monroe doctrine showed just how much nations could accomplish when they stopped quarreling and worked toward the same ends.

There is almost a fun-house mirror quality to the way that the current version of the doctrine has been stretched out of all resemblance to the original. Words like “democracy” and “self-determination” were noticeably absent in the White House version, the Donroe doctrine. The 2 December statement was all about strength, claiming that the “mighty words” from 1823 marked the beginning of a “superpower unlike anything the world had ever known”. That statement overlooks the inconvenient fact that in 1823, the United States had no power to enforce its doctrine, and relied entirely on the British navy at a time when the American navy was a fraction the size of France’s.

The Monroe doctrine was indeed a big deal when it was introduced, but not for the reasons being touted at the moment. In 1823, the United States was struggling to find its place in the world. It had fought two wars against the United Kingdom, including a recent one, between 1812 and 1815, that resulted in humiliation when British troops invaded the capital city of Washington DC, and torched most of the government buildings, including the Capitol and White House. The new country was growing quickly, but it could hardly be called a military threat to its neighbors. The US army had a little more than 6,000 troops, after a reduction in 1821. The navy had about 4,000. That total – 10,000 – is smaller than the number (12,000) Cyprus can mobilize today.

Making matters worse, the progress of democracy, begun with so much fanfare in 1776, seemed to be stalling. The French Revolution had thrown Europe into more than a decade of war and convulsion, and after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo, the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815) reasserted a conservative vision of Europe dominated by kings and all that went with them. Suddenly, the principles of republicanism were decidedly out of fashion. The new power structure was strengthened by the 1815 creation of a “Holy Alliance”, linking the extremely old-guard monarchies of Prussia, Austria-Hungary and Russia. Together, they were determined to make sure that there would never be another democratic revolution.

That put the United States at a disadvantage, except for the fact that John Quincy Adams was the secretary of state. The son of the second president, Adams had grown up in several European countries (his father, too, was a diplomat), and could speak French, Greek and Latin. He was variously the US minister to the Netherlands, Prussia, Russia and the Court of St James. At times, he lived in London, where he met and married his wife, Louisa Catherine Johnson, an American who had grown up in England.

In other words, Adams was well prepared, by training and temperament, to advance America’s interests. At the same time, he was willing to buck protocol. He was known to swim in the Potomac wearing nothing but a skullcap and goggles. Later, he would be a brave voice against slavery when most of the US government went the other way. This was not your ordinary diplomat.

Adams became secretary of state in 1817 and would stay until 1825, when he became president. In 1819, he negotiated the Adams-Onis treaty, which transferred a huge amount of land, peacefully, to the United States from Spain, which was impoverished by the Napoleonic wars. Without this treaty, which secured Florida, Mar-a-Lago would be in a foreign country today.

Adams also resolved a host of issues relating to the wars that had divided Great Britain and the United States. As a child, he had witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill, the first major engagement of the American Revolution. But as secretary, he helped to reduce tensions, charting the western boundary with Canada (then a part of the UK), and reducing naval armaments on the Great Lakes.

These acts of mutual respect improved relations, and the two powers began to see each other in a new light. In 1821 (the same year that the Guardian was founded), Adams gave a Fourth of July speech that praised the British, as a people “distinguished for their intelligence and their spirit”, and announced that the United States would never go abroad “in search of monsters to destroy”. In other words, Adams was announcing a policy of nonintervention – the opposite of Donald Trump’s interpretation of the Monroe doctrine. Although Adams was an expansionist in his own way – he felt that adjoining territories would eventually join the United States voluntarily – he was against the use of military threats to accumulate real estate.

The warming of Anglo-American relations continued, and two years later, in 1823, the British foreign minister, George Canning, approached the United States with a proposition. As Spain’s power continued to ebb, it was losing control of its colonies in the Americas, and local independence movements had achieved full or partial success in Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Chile and Argentina. This was troubling to the Holy Alliance, determined to fight the spread of democracy and maintain the rule of absolutism.

But it was not so troubling to Britain. Though a king, George IV, certainly sat on the throne, the British government was more open to a world with diverse forms of government, including democracies. It had a growing middle class, and a strong parliament that represented merchants, mill-owners, and the people at large. In fact, Canning, the son of an actor, was such a person himself.

Accordingly, Canning wondered if the United States and the United Kingdom might together indicate their joint support for the new republics, and warn the European powers not to send military expeditions into the Americas. Such a statement would bolster the new governments and deter any effort by Spain, France or the Holy Alliance to gain new colonies in the Americas.

Adams saw merit in the idea, and drafted a statement, now known as the Monroe doctrine, that was included in James Monroe’s annual message to Congress in December 1823. It asserted that the Americas “are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers”. It added that if European nations tried to impose “their system” – monarchy – anywhere in the Americas, the United States would regard it as “the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition”.

But it was hardly a sweeping statement of American power. It modestly promised that the US would not interfere in European affairs if Europe stayed out of the Americas. It did nothing to alter the status quo in the many places where European nations already possessed American colonies. And it needed the might of the British navy to be effective. In fact, no invasion from the Holy Alliance ever came, although Russia still had claims to the Pacific coast.

The new doctrine was welcomed by the leaders of Latin America’s independence movements, grateful for the help. It also brought the UK and the US together in a way that began to paint a way forward, for each, toward a world of greater freedom and rights, earned grudgingly, year by year.

That mutual understanding would pay dividends for both. It helped the United States that Britain, after some slowness, refused to recognize the Confederacy during the civil war. It helped the United Kingdom that the United States, after some slowness, put all of its might into the fight during two existential world wars.

The Monroe doctrine was not static during these years. It was a flexible instrument, serviceable for different messages. Expansionists could enlarge it into a call for aggressive action against the other countries of the Americas, as they did during the 1850s, when pro-slavery advocates argued that the US should acquire new territories around the hemisphere, and again in the 1890s, when the US plucked Cuba and Puerto Rico from Spain. The 20th century witnessed many interventions by presidents, well before Trump, in places ranging from the Dominican Republic to Haiti to Guatemala. That muscular approach feels closer to the Donroe doctrine.

But its better angels were also available, as when FDR’s secretary of state, Cordell Hull, promised a policy of nonintervention by the United States, and support for free trade and democracy, at a conference in Uruguay in 1933. That approach paid huge dividends when Latin America generally supported the allied cause in the second world war, and Venezuelan oil supplied allied convoys. Franklin D Roosevelt’s “good neighbor” policy was echoed by John F Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress, a program of economic cooperation, education and support for democracy.

A new order

Is Trump’s reformulation of the Monroe doctrine, in fact, a doctrine? His former national security adviser, John Bolton, recently told the Atlantic, “There is no Trump Doctrine: No matter what he does, there is no grand conceptual framework; it’s whatever suits him at the moment.” It’s also true that presidents do not generally get to name doctrines and corollaries after themselves; that takes time – and consensus (Monroe’s doctrine was not named after him until 30 years later).

Paradoxically, the closest thing to a recent doctrine was the speech delivered at the recent Davos meeting by Canada’s prime minister, Mark Carney. It has already been called the Carney doctrine.

Arguing for an alliance of the world’s “intermediate powers”, it proposed a “new order that encompasses our values, such as respect for human rights, sustainable development, solidarity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the various states”. It was coherent and pragmatic, seeking allies to resist a rising tide of reactionary thinking. That was very much in the spirit of John Quincy Adams and the original Monroe doctrine, a riposte to the great powers of its day, who were in their own way blind to the currents of history.

It was also, in its way, aligned with Bad Bunny’s half-time show. On the surface, the Canadian prime minister’s sober speech and the Puerto Rican singer’s rollicking performance could not be more different. But they hit many of the same grace notes. By acknowledging that we are not alone in this hemisphere, by naming so many nations – he proposed a radical way to make America, in the largest sense of the word, great again.

-

Ted Widmer is the author of Lincoln on the Verge: Thirteen Days to Washington (2020), and the editor of The Living Declaration: A Biography of America’s Founding Text, forthcoming from the Library of America (spring 2026).

-

Spot illustrations by Lucy Jones

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 hours ago

2 hours ago

Comments