President Donald Trump activated 4,000 National Guard troops on June 10, 2025, to quell protests in Los Angeles over immigration raids – without the normal request from the state. He has also sent to Los Angeles hundreds of U.S. Marines, with the goal of protecting the unprecedented deportation operations by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

If this all feels exceptional, it should. Governors typically activate their own state troops, as Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said he would do on June 11 ahead of expected immigration protests.

California quickly sued the president. A federal court has sided with the state, but an appeals court will weigh the Trump administration’s use of the U.S. code on armed services to activate the National Guard, which relies on protesters constituting either an “invasion” or “rebellion.”

“What we’re witnessing is not law enforcement – it’s authoritarianism,” California Gov. Gavin Newsom said on June 10.

Protesters report violent responses from Los Angeles police, too. Nonetheless, Newsom’s invocation of authoritarianism is apt.

The last example of a president federalizing troops over the objection of a state government dates to Jim Crow segregation, a period marked by legal practices that routinely denied due process and citizenship rights to Black Americans in the South. In the 1960s, numerous Black freedom struggles took stands against this authoritarianism backed by militarized law enforcement.

As a scholar of U.S. history, I’ve just completed a book on Jim Crow policing and the ways Black Americans fought back against racist law and order. I think the militarization of policing in Los Angeles opens important questions about democracy and state violence.

Jim Crow dreams

During the Civil Rights Movement, the federal government activated National Guard troops over Southern state objections when those states would neither enforce court orders nor protect protesters.

In those cases, presidents protected people with the help of troops. In Trump’s case, he’s using troops to protect the government from protesters.

The Trump administration’s vision of law enforcement aims for the type of militarized authority that state governments institutionalized under Jim Crow policing. If your political enemy is perceived more like an enemy combatant, the rules of legal procedure, especially due process, might not apply. Policing becomes war.

When you see the words “Jim Crow,” your mind may jump to photos of racially segregated water fountains. But Jim Crow was far more than that. It was homegrown racial authoritarianism, or the repression of freedom of thought and action.

Before troops enforced civil rights, Black Southerners saw the National Guard as an enemy rather than a friend.

In the words of Ida B. Wells-Barnett after a white riot against Black residents in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1917, “The police were either indifferent or encouraged the barbarities. … The major part of the National Guard was indifferent or inactive. No organized effort was made to protect the Negroes or disperse the murdering groups.”

Eisenhower sends in the troops

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education changed things. It overturned the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that legalized racial segregation and ruled that segregated public school education was unconstitutional. This significantly altered the federal government’s responsibility in the South’s legal system of white supremacy.

The first test came in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1957. Though numerous school districts across the South quietly desegregated, Southern governors such as Arkansas’ Orville Faubus resisted the planned desegregation of Little Rock Central High School.

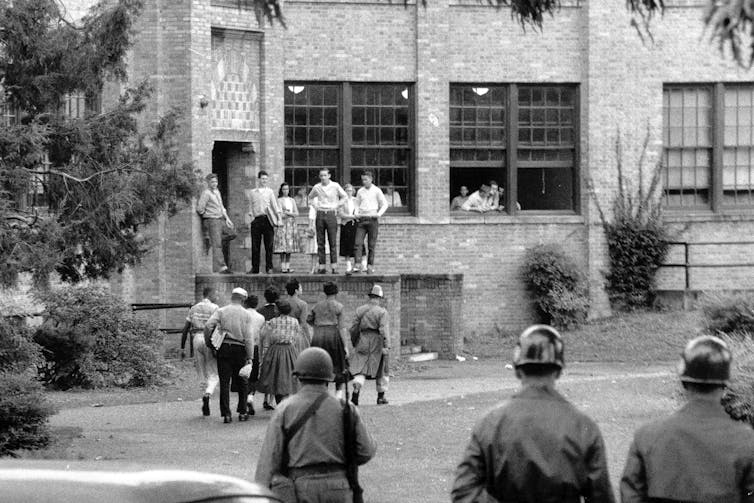

Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to stop Black children at the door. For nearly three weeks, Guardsmen blocked the small group of Black students – known as the “Little Rock Nine” – who were supposed to attend the school before President Dwight Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to stand down.

Eisenhower deployed U.S. Army riot troops to Little Rock under the Insurrection Act. In the end, the Little Rock Nine began their studies at Central High despite the much-photographed spitting from the white mob that surrounded the school.

State troops, state rights

Next came the desegregation of interstate transportation.

In spring 1961, the Congress of Racial Equality, a civil rights advocacy group, sent buses of integrated passengers through the Deep South. White terrorists attacked Freedom Riders, as these activists became known, three times in Alabama.

But state authorities had learned from the Little Rock experience. Southern governors in Alabama and Mississippi deployed the National Guard themselves. This time they intended to only minimally protect Freedom Riders to block federal law enforcement. In Mississippi, police arrested and prison guards tortured Freedom Riders in the state penitentiary. Mob violence killed no one.

The same was not true during the desegregation of public universities.

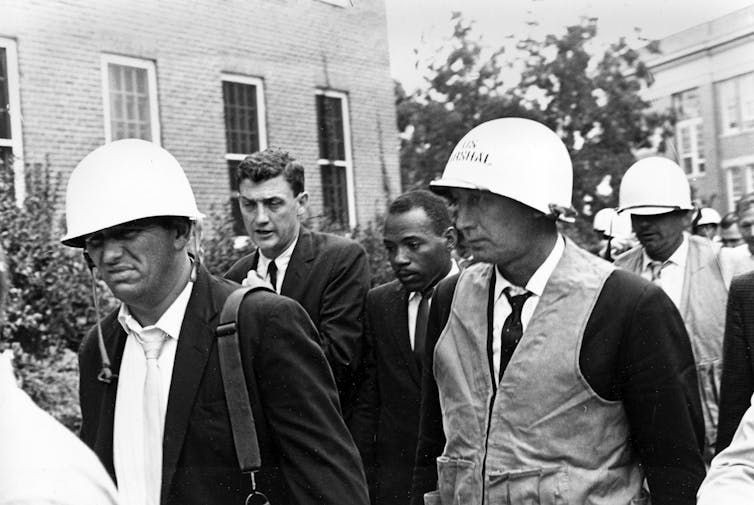

When U.S. marshals arrived to enforce the court order enrolling James Meredith at the University of Mississippi in September 1962, a white riot erupted. State law enforcement withdrew from the scene. Two men died, and many more were injured.

President John F. Kennedy federalized the Mississippi National Guard and sent them in to restore order. The next summer, he did the same in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, to preemptively halt a riot at the University of Alabama.

The occasion became a publicity stunt for Alabama Gov. George C. Wallace. He temporarily blocked the entrance to Foster Auditorium, intent on stopping the court-ordered registration of three Black students.

“I stand before you here today in place of thousands of other Alabamians whose presence would have confronted you,” Wallace said to federal authorities. A National Guard general said, “Sir, it is my sad duty to ask you to step aside under the orders of the President of the United States.”

Wallace also triggered the last federal use – until now – of the National Guard. Alabama’s Selma-to-Montgomery march began as a memorial to Jimmie Lee Jackson, a young Black civil rights activist who was killed by police on Feb. 26, 1965. The march became primarily a symbol for the year’s Voting Rights Act.

In an important change, President Lyndon B. Johnson federalized the National Guard to protect marchers. State troopers and sheriff’s deputies had terrorized marchers, including John Lewis, who was almost beaten to death on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965.

Democracy is in the streets

The history of the National Guard in the South is an important part of what’s unfolding in Los Angeles and across the nation.

For most of the National Guard’s history in the South, political leaders used domestic military power to preserve the interests of racial authoritarians, not racial egalitarians. Little Rock, Tuscaloosa, Selma: Those moments when troops protected racial justice protesters at home stand out as some of America’s most hopeful moments.

Recent statements by Trump administration officials help illustrate how it envisions using military power in domestic law enforcement. On June 8, 2025, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem asked Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth “to arrest rioters” – a request beyond the original order to protect ICE agents.

And on June 12, Noem said that “the military people that are working on this operation … are staying here to liberate the city from the socialist and burdensome leadership that this governor and that this mayor have placed on this country.”

The National Guard and Marines are reportedly protecting immigration enforcement. But what might happen if they directly interact with protests?

With diverse tactics, protesters are halting business as usual because they see a mass-deportation regime terrorizing and disappearing people in their communities. U.S. courts tend to agree with their analysis but seem powerless to enforce even basic due process rights for those detained by ICE.

These activists show the messy work of American social change. Their work may look like “anarchy” to even some Democrats. It may be maligned as “invasion” and “rebellion” by the Trump administration.

But the calls to constrain ICE follow an American tradition of fighting authoritarianism.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  7 hours ago

7 hours ago

Comments