The U.S. Supreme Court has always ruled on politically controversial issues. From elections to civil rights, from abortion to free speech, the justices frequently weigh in on the country’s most debated problems.

And because of the court’s influence over national policy, political parties and interest groups battle fiercely over who gets appointed to the high court.

The public typically finds out about the court – including its significant decisions and the politics surrounding appointments – from the news media. While elected officeholders and candidates make direct appeals to their voters, the justices and Supreme Court nominees are different – they largely rely on the news to disseminate information about the court, giving the public at least a cursory understanding.

Recently, something has changed in newspaper coverage of the Supreme Court. As scholars of judicial politics, political institutions and political behavior, we set out to understand precisely how media coverage of the court has changed over the past 40 years. Specifically, we analyzed the content of every article referencing the Supreme Court in five major newspapers from 1980 to 2023.

Of course, people get their news from a variety of sources, but we have no reason to believe the trends we uncovered in our research of traditional newspapers do not apply broadly. Research indicates that alternative media sources largely follow the lead of traditional beat reporters.

What we found: Politics has a much stronger presence in articles today than in years past, with a notable increase beginning in 2016.

When public goodwill prevailed

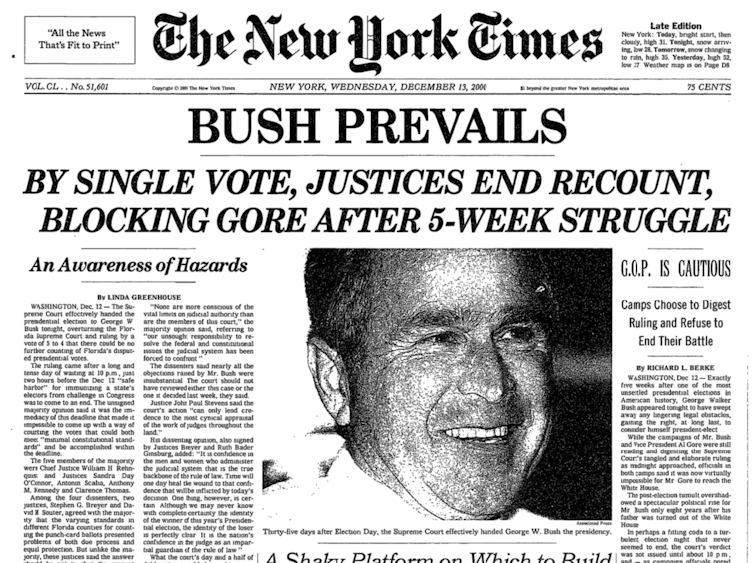

Not many cases have been more important in the past quarter-century or, from a partisan perspective, more contentious than Bush v. Gore – the December 2000 ruling that stopped a ballot recount, resulting in then-Texas Governor George W. Bush defeating Democratic candidate Al Gore and winning the presidential election.

Bush v. Gore is particularly interesting to us because nine unelected, life-tenured justices functionally decided an election.

Surprisingly, the court’s public support didn’t suffer, ostensibly because the court had built up a sufficient store of public goodwill.

One reason public support remained steady following Bush v. Gore might be newspaper coverage. Although the court’s decision reflected the justices’ ideologies, with the more conservative members effectively voting to end the recount and its more liberal members voting in favor of the recount, newspapers largely ignored the role of politics in the decision.

For example, the New York Times case coverage indicated the justices’ names and their votes but mentioned neither the party of the president who appointed them nor their ideological leanings. The words “Democrat,” “Republican,” “liberal” and “conservative” – what we call political frames – do not appear in the Dec. 13, 2000, story about the decision.

This epitomizes court-related newspaper articles from the 1980s to the early 2000s, when reporters treated the court as a nonpolitical institution. According to our research, court-related news articles in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times and The Wall Street Journal hardly used political frames during that time.

Instead, newspapers perpetuated a dominant belief among the public that Supreme Court decisions were based almost completely on legal principles rather than political preferences. This belief, in turn, bolstered support for the court.

Recent newspaper coverage reveals a starkly different pattern.

A contemporary political court

It would be nearly impossible to read contemporary articles about the Supreme Court without getting the impression that it is just as political as Congress and the presidency.

Analyzing our data from 1980 to 2023, the average number of political frames per article tripled. To be sure, politics has always played a role in the court’s decisions. Now, newspapers are making that clear. The question is when this change occurred.

Across the five major newspapers, reporting about the court has gradually become more political over time. That isn’t surprising: America has been gradually polarizing since the 1980s as well, and the changes in news media coverage reflect that polarization.

Take February of 2016, when Justice Antonin Scalia unexpectedly died. Of course, justices have died while serving on the court before. But Scalia was a conservative icon, and his death could have swung the court to the center or the left.

How the politics of naming his successor played out after Scalia’s death was unprecedented.

President Barack Obama’s nomination effort to put Merrick Garland on the court were stonewalled. The Senate majority leader, Republican Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, said the Senate would not consider any nomination until after the presidential election, nine months from Scalia’s death.

Republican candidate Donald Trump, seeing an opening, promised to fill the vacancy with a conservative justice who would overturn Roe v. Wade. The court and the 2016 election became inseparable.

Scalia vacancy changed everything

February 2016 brought about an abrupt and lasting change in newspaper coverage. The day before Scalia’s death, a typical article referencing the court used 3.22 political frames.

The day after, 10.48.

We see an uptick in political frames if we consider annual changes as well. In 2015, newspapers averaged 3.50 political frames per article about the Supreme Court. Then, in 2016, 5.30.

Using a variety of statistical methods to identify enduring framing shifts, we consistently find February 2016 as the moment newspapers shifted to higher levels of political framing of the court. We find the number of political frames in newspapers remained elevated through 2023.

How stories frame something shapes how people think about it.

If an article frames a court decision as “originalist” – an analytical approach that says constitutional texts should be interpreted as they were understood at the time they became law – then readers might think of the court as legalistic.

But if the newspaper were to frame the decision as “conservative,” then readers might think of the court as ideological.

We found in our study that when people read an article about a court decision using political frames, court approval declines. That’s because most people desire a legal court rather than a political one. No wonder polls today find the court with precariously low public support.

We do not necessarily hold journalists responsible for the court’s dramatic decline in public support. The bigger issue may be the court rather than reporters. If the court acts politically, and the justices behave ideologically, then reporters are doing their job: writing accurate stories.

That poses yet another problem. Before Trump’s three court appointments, the bench was known for its relative balance. Sometimes decisions were liberal; other times, conservative.

In June \2013, the court provided protections to same-sex marriages. Two days earlier, the court struck down part of the Voting Rights Act. A liberal win, a conservative win – that’s what we might expect from a legal institution.

Today the court is different. For most salient issues, the court supports conservative policies.

Given, first, the media’s willingness to emphasize the court’s politics, and second, the justices’ ideologically consistent decisions across critical issues, it is unlikely that the news media retreats from political framing anytime soon.

If that’s the case, the court may need to adjust to its low public approval.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  10 hours ago

10 hours ago

Comments