What may be one of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most important and far-reaching rulings in decades dropped in late May 2025 in an order that probably didn’t get a second – or even first – glance from most Americans.

But this not-quite-two-page ruling, as technical and procedural as they come, potentially rewrites a major principle of constitutional law and may restructure the operation of the federal government.

The case is dry in a way only lawyers could love, but its implications are enormous.

Public mission, not presidential whims

The dispute began when President Donald Trump fired two Biden-era officials: Gwynne Wilcox, a member of the National Labor Relations Board, and Cathy Harris, a member of the Merit Systems Protection Board.

The National Labor Relations Board and the Merit Systems Protection Board, like the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Reserve, are among more than 50 independent agencies established by Congress to help the president carry out the law. Though technically located within the executive branch, independent agencies are designed to serve the public at large rather than the president.

To ensure these agencies are devoted to their public mission, not the will or whims of a president, congressional statutes generally permit the president to remove leaders of these agencies only for “good cause.” Malfeasance in office, neglect of duty, or inefficiency generally constitute “good cause.”

Other executive branch agencies, such as the FBI, Food and Drug Administration and Department of Homeland Security are entirely under presidential command – if he wants their leaders out, out they go. But independent agencies, in existence since the late 19th century, are to carry out congressional policy free from the president’s purview and his political pressure.

Because independent agencies are creatures of Congress housed within the executive branch, there is long-standing disagreement among scholars about just how much power the president should have over them.

Limiting Congress, empowering the president

In the two firings, there was agreement that Trump had violated the relevant statute by firing Wilcox and Harris without “good cause.”

He justified Wilcox’s removal, in part, because she did not share his policy preferences. For Harris, he gave no reason at all.

But the bigger issue was whether the law itself was constitutional: Could Congress limit why or how a president can remove employees of the executive branch?

The root of the problem lies within the Constitution. Although Article 2 specifically gives the president the power to “appoint” certain federal officials, it says nothing about the power to fire -– or “remove” – them.

Conservative legal scholars propose, under what’s called the “unitary executive theory,” that because the president “is” the executive branch, he has complete authority, including removal, over all who serve within it. Only with the unfettered ability to fire anyone who serves under him can the president fulfill his constitutionally mandated duty to ensure that “the Laws be faithfully executed.”

Opponents have countered that this ignores fundamental aspects of our constitutional framework: the framers’ devotion to checks and balances, their aversion toward monarchical, kinglike rule, and their determination to put policymaking in the hands of Congress.

These questions are not new.

The Supreme Court first took up the issue in 1926 in Myers v. United States, when Chief Justice – and former president – William Howard Taft held that Congress could not limit the president’s ability to fire an Oregon postmaster, writing that “the power to remove inferior executive officers … is an incident of the power to appoint them.”

Less than a decade later, however, the court ruled in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States that the Constitution did not grant the president an “illimitable power of removal,” at least over certain types of officials. This included the head of the Federal Trade Commission, whose firing by President Franklin Roosevelt had sparked the case.

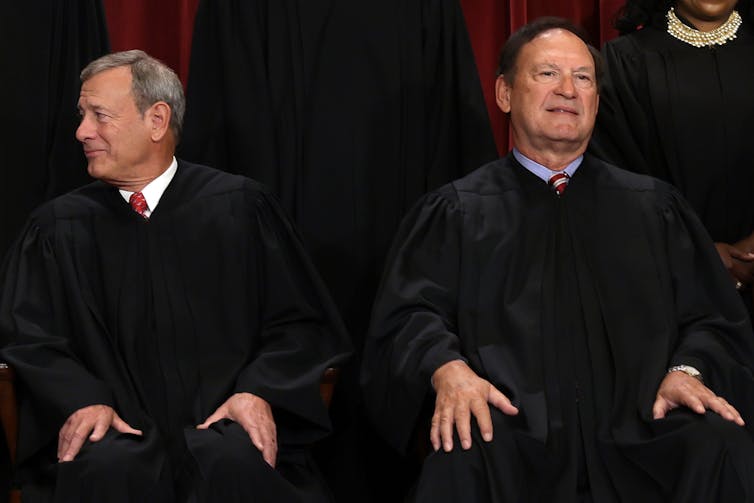

Humphrey’s Executor stood basically untouched for decades, until Justices John Roberts and Samuel Alito – both of whom had previously served in the executive branch – were appointed.

With a now-solid conservative majority, the Supreme Court invalidated restrictions on the president’s ability to remove members of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board in 2009.

Two years after the arrival of fellow executive branch alumnus Brett Kavanaugh in 2018, the court struck down the “good cause” removal restriction for the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Rather than explicitly overrule Humphrey’s Executor, however, the justices declared that these agencies were factually distinct from the Federal Trade Commission – leaders of one were protected by a “two-layer” removal system and the other because it was run by a single individual, not a multimember board.

‘Massive change in the law’

Because Humphrey’s Executor was still good law, and the National Labor Relations Board and the Merit Systems Protection Board were structured like the Federal Trade Commission, district courts in 2025 initially held that the firings of Wilcox and Harris were unlawful.

On April 9, 2025, Trump filed an emergency appeal with the Supreme Court, asking it to put the district court decisions on hold. On May 22, the Supreme Court granted that request, at least while the cases proceed through the lower courts.

The court did not decide on the constitutionality of the removal statute, but the ruling is nonetheless a major victory for Trump. He can now fire not only Wilcox and Harris but also potentially the heads of any independent agency. Low-level civil servants may also be at risk.

In the unsigned order, the high court echoed unitary executive theory, stating, “Because the Constitution vests the executive power in the Presidents … he may remove without cause executive officers who exercise that power on his behalf, subject to narrow exceptions.” It simply ignored Humphrey’s Executor altogether, leaving its value as precedent unclear.

The Supreme Court also said that the holding did not apply to the Federal Reserve Board. That “uniquely structured, quasi-private entity” would remain free from executive control via removal.

Such an explicit carve-out in legal doctrine is striking but responds directly to claims made by litigants and political commentators of the dire economic consequences that could result were the president to have free rein over the Federal Reserve’s chairman.

In dissent, Justice Elena Kagan blasted the majority for allowing the president to overrule Humphrey’s Executor “by fiat,” a result made even worse because the court had done so via the so-called shadow docket, in the absence of full briefing or oral argument. Such “short-circuiting” of the “usual deliberative process” is, she wrote, a wholly inappropriate way to make a “massive change in the law.”

The shadow of Humphrey’s Executor

What happens now?

The National Labor Relations Board is paralyzed, and the Merit Systems Protection Board is somewhat hamstrung, with both lacking the quorum necessary to act. Cases about the firing of Harris, Wilcox and multiple other officials will bedevil lower courts as they try to figure out whether Humphrey’s Executor still stands, even as a shadow of its former self.

Trump aims to continue axing federal employees, even as the administration struggles to rehire others.

And, already asked again to make major legal change on its emergency docket, the Supreme Court will need to determine whether such change warrants more than the few paragraphs of explanation it gave in the ruling on the Wilcox and Harris firings.

If, as seems likely, the court ultimately overturns Humphrey’s Executor, Kagan’s dissent serves as a warning voiced by others as well: A decision that allows the president to have total control over the heads of more than 50 independent agencies – agencies that pursue the public interest in areas from financial regulation to the environment, to nuclear safety – could shift their focus from serving the public to pleasing the president, profoundly affecting the lives of many Americans.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  20 hours ago

20 hours ago

Comments