In March 2024, six months into Israel’s war in Gaza, education in the territory was decimated. Schools were closed – most had been turned into shelters – and all 12 of the strip’s universities were partially or fully destroyed.

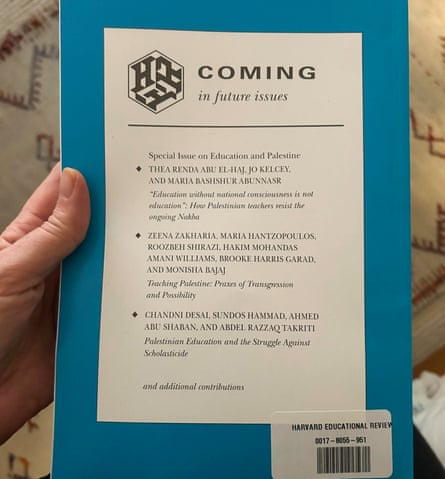

Against that backdrop, a prestigious American education journal decided to dedicate a special issue to “education and Palestine”. The Harvard Educational Review (HER) put out a call for submissions, asking academics around the world for ideas for articles grappling with the education of Palestinians, education about Palestine and Palestinians, and related debates in schools and colleges in the US.

“The field of education has an important role to play in supporting students, educators, and policymakers in contextualizing what has been happening in Gaza with histories and continuing impacts of occupation, genocide, and political contestations,” the journal’s editors wrote in their call for abstracts.

A little more than a year later, the scale of destruction in Gaza was exponentially larger. The special issue, which was slated to be published this summer, was just about ready – contracts with most authors were finalized and articles were edited. They covered topics from the annihilation of Gaza’s schools to the challenges of teaching about Israel and Palestine in the US.

But on 9 June, the Harvard Education Publishing Group, the journal’s publisher, abruptly canceled the release. In an email to the issue’s contributors, the publisher cited “a number of complex issues”, shocking authors and editors alike, the Guardian has learned.

US universities have come under intensifying attacks from the Trump administration over accusations of tolerating antisemitism on campuses. Many have responded by restricting protest, punishing students and faculty outspoken about Palestinian rights, and scrutinizing academic programmes home to scholarship about Palestine.

But the cancellation of an entire issue of an academic journal, which has not been previously reported, is a remarkable new development in a mounting list of examples of censorship of pro-Palestinian speech.

The Guardian spoke with four scholars who had written for the issue, and one of the journal’s editors. It also reviewed internal emails that capture how enthusiasm about a special issue intended to promote “scholarly conversation on education and Palestine amid repression, occupation, and genocide” was derailed by fears of legal liability and devolved into recriminations about censorship, integrity and what many scholars have come to refer to as the “Palestine exception” to academic freedom.

Paul Belsito, a spokesperson for the Harvard Graduate School of Education, wrote in a statement to the Guardian that the decision to cancel the special issue followed nine months of conversations and an “overall lack of internal alignment” about the issue.

The authors see it differently. “If the universities – or in this case a university press – are not willing to stand up for what is core to their mission, I don’t know what they’re doing. What’s the point?” said Thea Abu El-Haj, a Palestinian-American anthropologist of education at Barnard College, the women’s school affiliated with Columbia University, who was one of the solicited authors.

Harvard has been embroiled in a bitter battle with the Trump administration over millions in federal funding cuts and the revocation of its eligibility to host international students. In April, it became the first and so far only university to sue the administration, earning praise for its resistance to Trump’s onslaught.

But Harvard has also cracked down on Palestine scholarship, demotings scholars and canceling related programs. “Harvard is being held up as the heroic institution, but what’s happening internally is much more complicated,” said El-Haj.

In January, as part of a legal settlement with Jewish students who had accused Harvard of tolerating and promoting antisemitism on campus, the university adopted a controversial definition that critics argue conflates antisemitism with criticism of Israel.

In an email to the authors announcing the cancellation, the executive director of the publishing group did not cite antisemitism; she wrote the decision stemmed from what she described as an inadequate review process and the need for “considerable copy editing”.

The journal’s editorial board rejected that characterization and said they had been sidelined by the publisher in making the decision. The decision to cancel the issue was “out of alignment with the values that have guided HER for nearly a century”, the board members wrote in a collective statement.

The announcement came after the publishers had demanded that the articles be submitted to a legal review late into the process – a step the authors found highly unusual and called a “dangerous form of institutional censorship” in a joint letter objecting to the demand. The publisher’s request was prompted by fear the issue would attract antisemitism claims, said one editor.

The dispute underscores the unprecedented restraints placed on knowledge production amid escalating accusations of antisemitism on campuses and the Trump administration’s crusade against higher education. But it also signals the levels to which universities are abandoning their stated commitments out of fears of legal or financial repercussions.

“Even within the broader landscape around Palestine in the university, it’s unprecedented,” said Chandni Desai, a professor at the University of Toronto and author of one of the scrapped articles. “You just don’t solicit work, peer review it, have people sign contracts, advertise the articles, and then cancel not just one article, but an entire special issue.”

Tensions boil over

The Harvard Educational Review is a century-old academic journal that publishes research and opinion geared to education academics and professionals and is considered a leading publication in the field. It is published by the Harvard Education Publishing Group, a division of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and edited by doctoral students at the university.

The Palestine issue was slated to include a dozen research articles, essays and other writings on topics ranging from education in Israel-Palestine and among the Palestinian diaspora, to academic freedom in the US. They explored the evolution of the concept of “scholasticide”, a term describing the systematic annihilation of education first coined during Israel’s 2008 invasion of Gaza; the “ethical and educational responsibilities” of English language teachers in the West Bank; and the impact of “crackdowns on dissent” on teaching about Palestine in US higher education institutions, according to finalized abstracts of the articles shared with the Guardian.

Abu El-Haj’s piece, co-authored with two other scholars, explored the “centrality of education in the struggle for Palestinian liberation”, drawing from an oral history project on the experiences of teachers with the UN agency for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. The journal’s editors were so enthusiastic about her piece that last spring they selected it with two others to promote the upcoming special issue on the back cover of the spring one.

The special issue was also formally announced at an annual gathering of education scholars in Chicago in March. “There was quite a lot of interest in it,” said Jo Kelcey, a professor at the Lebanese American University in Beirut and one of Abu El-Haj’s co-authors.

The authors received the first inkling of trouble shortly after that.

Rabea Eghbariah, a Palestinian doctoral candidate at Harvard Law School, had been solicited to write the afterward for the special issue. In 2023, a different Harvard journal, the Harvard Law Review, had blocked publication of an article it had commissioned from him. When the Columbia Law Review published the piece instead, that journal’s board responded by temporarily shutting down its entire website. Wary of that experience, Eghbariah specifically requested to amend his contract with the Harvard Educational Review to add a clause seeking to safeguard his academic freedom. After a long silence, the journal declined his request in April.

“It is incredibly shameful to see a university publication so explicitly betraying its mission and rejecting a clause on protecting academic freedom,” said Eghbariah, who did not sign the contract. “My afterward specifically is about Nakba denialism – the phenomenon of manipulating facts to affirm Zionism and shape knowledge with regards to Palestine – and it is quite ironic that it is being denied publication.”

Days after their response to Eghbariah, the journal’s editorial board wrote to the authors, citing an “increasingly challenging climate” and asking for their availability for a meeting, which never ended up happening. “As a part of a scholarly community deeply committed to uplifting Palestinian voices and scholarship, we are facing some increasingly unprecedented contexts,” they wrote.

The email offered little detail, but for weeks, the journal’s editors had been under mounting pressure from the publisher. In January, they were told that an “institutional review” of the manuscripts would be required. In February, the publisher tried – without the editors’ knowledge – to alter the back cover of the spring issue promoting some of the forthcoming articles, according to email correspondence reviewed by the Guardian. (The printing company flagged the change to the editors, who reversed it.) In conversations with the editors – although not in writing – the publisher acknowledged that it was seeking a “risk assessment” legal review by Harvard’s counsel out of fear the issue’s publication would prompt antisemitism claims, an editor said.

As tensions came to a head, the board again contacted the authors in early May, to inform them of the requested legal review.

It was an extraordinary demand, the authors and editor interviewed by the Guardian said. Legal reviews would sometimes be requested for a specific article when there’s a libel concern – but early in the process, and not for an entire issue, they noted.

“This doesn’t happen, certainly not at the point where you’ve been accepted for publication and you’ve signed contracts,” said Kelcey. “This is not the way scholarship is supposed to operate.”

By then, the Trump administration had upended higher education by threatening billions of dollars in funding from universities in the US over their responses to pro-Palestinian protests. Harvard had sued in April, escalating its feud with the president. The authors, who hadn’t initially been in touch, found each other and organised a collective response, slamming the request for a legal review at that stage as “unprecedented”, they wrote in a 15 May letter to the journal’s editorial board and publisher. “This sends a dangerous message to scholars globally: that academic publishing contracts are conditional, revocable, and subject to external political calculations.”

The authors asked for the legal review to be reconsidered. But less than a month later, the press’s executive director, Jessica Fiorillo, wrote to them that the issue was being pulled altogether. In an email seen by the Guardian, she claimed the manuscripts were “unready for publication”, in part due to a copyeditor’s resignation. She also cited an unspecified “failure to adhere to an adequate review process”, a “lack of internal alignment” between the authors, editors and the publisher, and “the lack of a clear and expedient path forward to resolving the myriad issues at play”.

“This difficult situation is exacerbated by very significant lack of agreement about the path forward, including and especially whether to publish such a special issue at this time,” she wrote.

The copyediting issue wasn’t just a personnel one. The publisher’s letter claimed that the review editors “provided highly restrictive editing guidelines to the copy editor under contract to work on the special issue, limiting her focus to grammar, punctuation, and syntax errors, and directing her to refrain from offering any editorial suggestions to address, in the editors’ words, ‘politically charged’ content”. It claimed that the copyeditor resigned in large part because of those restrictions.

Fiorillo added that it would be “entirely appropriate” to subject the work to legal checks for “any libelous or unlawful material” but that no such review had taken place. She added that the cancellation was not “due to censorship of a particular viewpoint nor does it connect to matters of academic freedom”.

A ‘deep loss’

The journal’s editors were blindsided. “The Editorial Board has not been made privy to any internal decision-making at HEPG regarding the Special Issue, and we only learned about this communication and decision 30 minutes before it was sent out,” they wrote to the authors shortly after Fiorillo’s email.

In a longer letter to the authors, two days later, they rebutted Fiorillo’s claims about irregularities in the review process and expressed disappointment with the decision to cancel the issue.

“It is a deep loss that your work will not appear in the pages of [Harvard Educational Review] as we intended – for HER, for the field of education, and for social justice,” they wrote.

Regarding the publisher’s claim regarding overly restrictive copyediting guidelines, the editors said that they were asked by the publisher to develop copyediting guidelines – something that hadn’t been required for previous issues – and that they invited feedback at multiple points in the process.

It’s not clear how far up within Harvard’s administration the decision to cancel the issue had come from. Belsito, the spokesperson for the Harvard Graduate School of Education, wrote that Harvard’s Office of the General Counsel does not “make or direct editorial decisions” for the school or its publishing group.

“HEPG acknowledges the disappointment this decision may have caused for the authors and remains deeply committed to our robust editorial process, only publishing work of the highest scholarly quality through a process rooted in integrity, collaboration, and editorial rigor,” he added.

The Harvard chapter of the American Association of University Professors which got involved after learning about the cancellation, believe the decision came from the publisher.

“To us, it sounded like a textbook example of the killing of speech and academic inquiry related to Palestine,” said Kirsten Weld, a history professor and the chapter’s president. “Thus far, though our fact-finding remains incomplete, it looks like the impetus came from Harvard Education Publishing Group.”

One of the editors of the Harvard Educational Review, who asked for anonymity citing the repressive climate in academia, said that the pressure from the publisher on the editors ramped up shortly before Trump took office. The request to subject the entirety of the edited manuscripts to a risk assessment was “totally abnormal” the editor said. “I didn’t even know the [Office of the General Counsel] review was an option, I had never heard of it.”

The censorship of the issue, the editor added, is “exactly how authoritarianism grows”.

The members of the editorial board who worked on the issue said that they had done their best to “advance this work amidst a climate of repression and institutional accommodation”.

“As we reflect on this moment, we urge the scholarly community to defend the ability to publish rigorous, justice-oriented scholarship without interference and repression,” they added.

The ordeal is a “test case” for academic freedom, said Desai, whose article on scholasticide, co-written with three Palestinian colleagues, was also directly solicited and advertised on the back of the spring journal issue. (It was the teaser to her article that the publishers tried to remove from the back of the previous issue, without the editors’ knowledge.)

Desai criticized the cancellation as a “serious breach and violation of academic freedom and integrity” but also an affront to the labor of scholars who are “writing these articles during a genocide”.

She and her co-authors, including a dean at Al-Azhar University in Gaza, are not merely documenting the resilience of Palestinian education amid the destruction but are personally involved in those efforts, she noted. Many of their colleagues and students were killed as the group worked on the article. “This is not some abstract academic exercise,” said Desai. “I can’t keep stressing the urgency of this article as we’re watching universities being blown up.”

The authors are in talks with other journals and hope their pieces can be published together as planned. All those interviewed by the Guardian expressed fear that the incident will deter other scholars from pursuing work on Palestine – a longstanding problem that they say has only been exacerbated over the last two years. “There’s this risk of kind of closing down the democratic space,” said Kelcey.

As Israel and Palestine have become the flashpoint for a rapidly deteriorating climate for free speech and academic freedom in the US, Harvard has already demoted two faculty members leading the Center for Middle Eastern Studies (one of whom wrote the forward for the cancelled issue), suspended a partnership with Birzeit University in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, and ended a divinity school initiative dedicated to the conflict.

Scholars fear that the the capitulation of universities is hurting an entire field of study at the time when it’s most needed. But Abu El-Haj warned that the special issue’s cancellation also sets a dangerous precedent for the independence of scholarship on a variety of subjects. She accused the publisher of “anticipatory compliance” and warned that “it’s not going to stop with Palestine,” she said.

But she also sounded a note of optimism. In a sign of the growing chasm between decision-makers and the broader public on the issue, she said that the war in Gaza has led to unprecedented interest among students in Palestine coursework and scholarship.

She recalled being a student in the US during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon and the massacres in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila by Israeli-backed Lebanese militias. “There were three of us protesting,” she recalled. “I never would have imagined in my life I’d see the encampments that happened last year.”

“We’re in a really critical juncture,” she added. “The level of repression that we’re seeing is related to the shift in the narrative, and the loss of control over that narrative.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  7 hours ago

7 hours ago

Comments