In the wake of the U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities on June 22, 2025, many congressional Democrats and a few Republicans have objected to President Donald Trump’s failure to seek congressional approval before conducting military operations.

They note that Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war and say that section required Trump to seek prior authorization for military action.

The Trump administration disagrees. “This is not a war against Iran,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio told Fox News host Maria Bartiromo, implying that the action did not require approval by Congress. That’s the same view held by most modern presidents and their lawyers in the Office of Legal Counsel: Article 2 of the Constitution allows the president to use the military in certain situations without prior approval from Congress.

By this reading of the text, presidents, as commander in chief, claim the power to unilaterally order the military to initiate small-scale operations for a short duration. Members of Congress may object to that claim, but they have done little to limit presidents’ unilateralism. What little they have done has not been effective.

As I’ve demonstrated in my research, even though the 1973 War Powers Resolution attempted to constrain presidential power after the disasters of the Vietnam War, it contains many loopholes that presidents have exploited to act unilaterally. For example, it allows presidents to engage in military operations without congressional approval for up to 90 days. And more recent congressional resolutions have broadened executive control even further.

A long tradition of executive authority

Presidents can even overcome the loopholes in the War Powers Resolution if the operation lasts longer than 90 days. In 2011, a State Department lawyer argued that airstrikes in Libya could continue beyond the War Powers Resolution’s 90-day time limit because there were no ground troops involved. By that logic, any future president could carry out an indefinite bombing campaign with no congressional oversight.

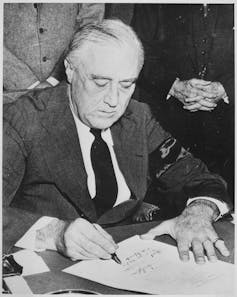

While every president has bristled at congressional restraints on their actions, presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt have successfully circumvented them by citing vague concerns like “national security,” “regional security” or the need to “prevent a humanitarian disaster” when launching military operations. While members of Congress always take issue with these actions, they never hold presidents accountable by passing legislation restraining him.

President Trump’s decision to bomb Iranian nuclear sites without consulting Congress falls in line with precedent from both Democratic and Republican leaders for decades.

Much like his predecessors, Trump did not, and likely will not, provide Congress with more concrete information about the legality of his actions. Nor are congressional lawmakers effectively holding him accountable.

The push-and-pull between Congress and the president over military operations dates back to the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, which led Congress to declare war on Japan. Before then, Congress had prevented the U.S. from joining World War II by enforcing an arms embargo and refusing to help the Allies prior to the attack on Hawaii. But afterward, Congress began allowing the president to take more control over the military.

During the Cold War, rather than returning to a balanced debate between the branches, Congress continued to relinquish those powers.

Congress never authorized the war in Korea; Harry Truman used a U.N. Security Council resolution as legal justification. Congress’ vote explicitly opposing the invasion of Cambodia didn’t stop Richard Nixon from doing it anyway. Even after the Cold War, Bill Clinton regularly acted unilaterally to address humanitarian crises or the continued threat from leaders like Saddam Hussein. He sent the military to Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo, among other places.

After 9/11, Congress quickly gave up more of its power. A week after those attacks, Congress passed a sweeping Authorization for Use of Military Force, giving the president permission to “use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001.”

In a follow-up 2002 authorization, Congress went even further, allowing the president to “use the Armed Forces … as he determines to be necessary and appropriate in order to defend national security … against the continuing threat posed by Iraq.” This approach provides few, if any, congressional checks on the control of military affairs exercised by the president.

In the two decades since those authorizations, four presidents have used them to justify all manner of military action, from targeted killings of terrorists to the years long fight against the Islamic State group.

Congress regularly discusses terminating those authorizations, but has yet to do so. If Congress did, the loopholes in the original War Powers Resolution would still exist.

While President Biden claimed he supported the repeal of the authorizations, and supported more congressional oversight of military actions, Trump has made no such claims. Instead, he has claimed even more sweeping authority to act without any permission from Congress.

As recently as 2024, Biden used the 2002 authorization as a legal rationale for the targeted killing of Iranian-backed militiamen in Iraq, a strike condemned by Iraqi leaders.

Those actions may have ruffled congressional feathers, but they were in keeping with a long U.S. tradition of targeting members of terrorist groups and protecting members of the military serving in a conflict zone.

Threats of war

During his first presidential term in 2020, Trump ordered a lethal drone strike against a respected member of the Iranian government, Major General Qassim Soleimani, the head of Iran’s equivalent of the CIA, without consulting Congress or publicly providing proof of why the attack was necessary, even to this day.

Tensions – and fears of war – spiked but then slowly faded when Iran responded with missile attacks on two U.S. bases in Iraq.

Now, the U.S. attacks on Iranian nuclear sites have revived both fears of war and renewed questions about the president’s authority to unilaterally engage in military action. Presidents since the 1970s, however, have effectively managed to dodge definitive answers to those questions – demonstrating both the power inherent in their position and the unwillingness among members of the legislative branch to reclaim their coequal status.

This article is an updated version of a story published on Jan. 24, 2024.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  6 hours ago

6 hours ago

Comments