The night before Mahmood Mamdani was expelled from Uganda in 1972, a senior professor from the university where he had been employed as a lowly teaching assistant wandered into his family home, looking for spoils. The rest of the family had already left – for the UK, the US and Tanzania – but 26-year-old Mamdani had decided to remain until the final day of the three-month period that Idi Amin, the Ugandan president, had designated for all Asians to leave the country. Passing over the furniture and other remnants of decades of family life, the professor hit upon a carton of Johnnie Walker Red, which Mamdani invited him to take home.

The next day, reunited with his parents at a transit camp in London, Mamdani learned that the bottles had in fact held nothing but cooking oil, and he amused himself imagining the professor serving them at a party to celebrate the forced departure of tens of thousands of south Asians. It was only later that the “loneliness, anxiety [and] depression” of expulsion set in. Mamdani would go on to join the vibrant intellectual community in Dar es Salaam, where his superfluity of study groups was populated by a who’s who of pan-African scholars and politicians; his parents settled in Wembley, in north-west London, where for several years their “favorite pastime” was greeting the weekly flight from Uganda to Gatwick airport in hopes of meeting a former acquaintance.

“Every place we lived in after the expulsion, we lived as if we were guests, our houses or rooms stamped with the feeling of being transients,” Mamdani writes in his book Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni, and the Making of the Ugandan State, published this October. “With the loss of Uganda, we lost a sense of belonging, and of rootedness.”

The question of who belongs in a political community has animated Mamdani’s scholarship ever since. Now a professor of anthropology at Columbia University, Mamdani has gained recent notoriety (alongside his wife, film director Mira Nair) as the father of Zohran Mamdani, the New York City political phenomenon and mayor-elect. But his long career and extensive bibliography attest to a lifetime interrogating the colonial categories that continue to define and divide postcolonial politics: race, tribe, Indigeneity; citizen, settler, subject.

In Slow Poison, Mamdani turns his attention back to the nation that he has always considered his home, even when it wouldn’t have him. The book combines memoir, history and political theory to reassess two men who have defined Uganda since it achieved independence from the UK in 1962: Amin and Yoweri Museveni. It also grapples with big questions with contemporary relevance: who chooses our global villains, and why? How do notions of Indigeneity operate in a world where people always have migrated – and always will? Who gets to decide which people belong, and deserve rights, in a given country?

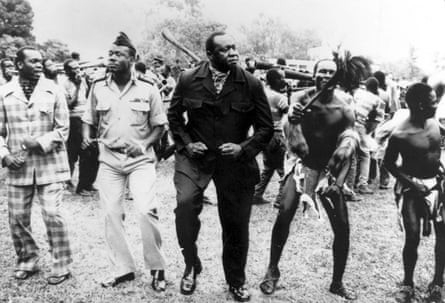

Amin is primarily known to westerners as a brutal dictator and rumored cannibal, but he enjoyed significant popular support in Uganda from the time he took power in a 1971 coup until he was overthrown in 1979. Mamdani attributes this in part to his expropriation and expulsion of the country’s 80,000 Asian people – most of them the descendants of Indian immigrants who arrived during British colonial rule – in an act of racial nationalism that helped unite Uganda’s disparate ethnic groups and tribes in a shared Black identity.

Museveni, a onetime Marxist and devotee of Frantz Fanon who frequented the same intellectual circles as Mamdani in Dar es Salaam, took power in 1986 and has yet to relinquish it. His increasingly authoritarian regime has been characterized by extreme corruption, regional conflicts and human rights violations, Mamdani argues, but “whereas the British propaganda machine turned Amin into a monster and Asians his global victims, Museveni became a Washington poster boy”.

The disparate treatment is a result of the two men’s stances toward the west, Mamdani argues. Amin seized power with the backing of the UK and Israel – the UK maintained a strong interest in its former colony, while Israel sought an ally that would allow it to build a military base to the south of Egypt – but turned on them soon after taking power. This about-face saw Amin align himself with Muammar Gaddafi to support Palestinian rights and the boycott of apartheid South Africa, and thumb his nose at the west. By contrast, Museveni acceded to the neoliberal demands of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, and signed on to the US’s “war on terror”, providing it crucial regional support in east Africa.

But Mamdani’s larger concern is with Museveni’s “continuous fragmentation of the subject population” of Uganda into ever smaller tribal divisions, with people designated “Indigenous” or “non-native” within ever smaller parcels of land. The 1993 Uganda Constitutional Commission defined “Indigenous” groups as those that could trace their presence in Uganda to three or four generations back and could also “indicate ancestral burial grounds and land within Uganda”; Museveni’s program of subdivision saw more and more Ugandans recast as “settlers” if they lived outside their assigned district – a designation that deprived them of the right to own land or hold high political office.

Whereas Amin had united Uganda’s ethnic and linguistic groups into one racial category, Museveni has used those differences to fragment the populace and keep any threat to his power at bay. This process is the “slow poison” that Mamdani asserts is killing Uganda’s body politic.

There is a clear connection between Mamdani’s appeal for a politics that respects cultural difference while preserving universal equal rights, and the campaign run by his son, who prevailed despite his steadfast refusal to support Israel’s political system, which denies equal rights to millions of Palestinians who are subject to its rule.

“The challenge is how to reconcile cultural identity with political belonging, and a common past with a shared future,” Mamdani writes. “Not all who share a common past necessarily share a common future: some may migrate and become part of a diaspora. At the same time, people with different pasts can commit themselves to building a common future in the same place. This is why those who wish to build a future under a single political roof – no matter how different their pasts – belong to the same political community and thus deserve the same political rights.”

A week after Zohran’s triumph in the New York City mayoral election signaled a new generation of Americans’ embrace of such universalist values, the elder Mamdani spoke with the Guardian about his history, his politics and his hopes for the future.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In your new book, you are asking people to reconsider Amin and the way that he has been portrayed as a kind of Hitler-esque figure. Why was it important to you to return to this history now?

The western media in particular has been central to describing Amin as “the cannibal Amin”, etc – and without going to the other extreme of providing an apology [for Amin’s regime], as the Wall Street Journal thinks, I thought it was important to situate Amin in a context and to get a sense of him. Amin is trained as a child soldier by the British. He becomes a specialist in counter-terrorism, which is really a polite term for state terrorism.

The worst of Amin’s killings, which are in the hundreds, and you might even say in the thousands, take place in the first year after he takes power. Those killings are informed, guided by the British and the Israelis. The British advise Amin to assassinate [then president Milton] Obote on arrival. The Israelis disagree. They say: “No, [if] you do that you will leave the military power structure intact, and there will be a reckoning down the road.” So Amin follows the Israeli advice and he carries out massacres in barracks. That’s Amin at his most brutal. [Note: estimates of Amin’s death toll range from 12,000 to 500,000; in Slow Poison, Mamdani argues that western sources inflated Amin’s brutality for political reasons.]

At the same time, Amin is disturbed at the general lawlessness spreading throughout the country, and appoints a commission of inquiry into disappearances. It’s the first truth commission that I know in the contemporary era. The commission recommends that the police take charge of civil order, and that army control of key institutions be negated.

So that’s Amin: a complicated character. The shift between these two phases is informed by Amin’s understanding. After his first visits to Israel and London, it dawns on him that neither the British nor the Israelis take him seriously. They both think that he should be grateful and act as a stooge. That’s his big turning point. The British try to overthrow him. The Israelis try. The important point is that Amin becomes very popular in the country and the attempts to overthrow him from the outside do not work.

Why is it important to scrutinize Israel’s role in this history?

Israel’s role in Uganda in particular was critical. Israel cultivated Amin right from the beginning. Israel thought he would be their man. They built houses for him. They anointed him in Hebrew. They trained the forces which were central in making the coup. They advised him to use those forces and only those forces. They advised him on how to deal with the Obute military opposition.

And then, of course, they were completely surprised when he [switched allegiances]. This is a very central role. This is not singling out Israel. If one didn’t talk of Israel, you would have no explanation of what happened.

You describe Uganda under Museveni as a junior version of Israel. Can you explain what you mean?

What I mean by junior version of Israel is a state which carries out, in particular, military missions in the region, in one country after another at the urging of or with the approval of the US, and in return gets a clean pass on everything else, and is guaranteed impunity. That’s Israel on a larger scale, and that’s Museveni on a regional scale.

Many of us are accustomed to thinking of “Indigenous rights” as an important counterweight to the legacy of colonialism, but you have long questioned the meaningfulness of the distinction between “Indigenous” and non. Why is it important to you to interrogate the concept of Indigeneity as you think about who belongs in a political community?

I first encountered this question in a book I wrote several decades ago called Citizen and Subject. I was puzzled by the political architecture that Britain created in its colonies to govern. The census tagged every person living in a colony as belonging either to a race or to a tribe, and I was curious: what’s the distinction? I realized that a race was anybody who had come from outside, who was not Indigenous, and a tribe was anybody who was Indigenous. So I asked myself: “What difference does it make?” Well, it made a difference in how they were governed under the law. All races, whether they came from Europe or from south Asia, anywhere, were governed under the same law, civil law. To be governed under the same law meant that you were supposed to have a common future.

Tribes were not governed under the same law. First of all, there was the fiction that each tribe had a homeland. I call this a fiction because it’s not true. Before colonialism, not only Africans, but humans have been migrants. You cannot peg humans to a particular piece of territory over centuries and millennia. You can’t. They’ve moved. This fiction that every tribe had a homeland was extended so that every homeland had a customary authority. Cultural authorities were turned into political authorities. And then the British created something called customary law, which could be enforced by customary authorities with British power standing behind them. This made for a separate future for the tribes, unlike the races. I understood this to be the political, legal essence of what we normally call “divide and rule”.

When I went to South Africa in 91, I was writing a book on Africa. Every chapter was written, except one chapter on south Africa, because south Africa was supposed to be the exception. Apartheid was supposed to be the exception. And after just a very little time in South Africa, I realized that I’d been totally mistaken. I’d been misled. South Africa was not an exception. I knew this beast. I had grown up under it in Uganda, although you may call it an informal version of apartheid. It was the same thing where the state used law to divide the population into different groups and privileged one section of the population at the expense of the other. I began to come to a conclusion that every modern colony was an apartheid state.

The book deals with your personal history and how your identity cuts across the lines that have been drawn to divide groups for various reasons, whether as an Asian within Uganda or a Muslim from Gujarat in India. The policing of those lines was brought home in a particularly personal way this summer, when the New York Times ran an article seeking to scandalize the fact that your son had attempted to reflect his identity as African and Ugandan on his college application.

I was pretty shocked to see that the Times had contacted you to ascertain whether you had any ancestry from Black Africans. It seemed to invoke the “one drop” rule of Blackness, which is very American, as well as Amin’s view that Asians are not really Ugandan. What did you make of that controversy? How do you see the policing of identity categories in the US compared to Uganda and other post-colonial states?

In 2013 we formed an organization in Kampala called the Asian African Association. We said in our opening declaration Asian Africans are people whose past is Asian, but whose future is African. They are Africans of Asian descent. We said that in the past we had always lived as visitors, or even worse, as refugees, which meant that we had neither rights nor responsibilities. We were permanently on vacation or permanently entrepreneurs.

The formation of this organization was part of a much larger quest which runs through African nationalist struggles, which was: who belongs? Who is part of the nation and who is not? The whole South African conception which ends with the notion of a non-racial South Africa – obliterating the boundary between Indigenous and non-Indigenous – is a fruit of that struggle, and it’s a legacy that we embraced.

Now the New York Times – it was scandalous to me that they were resurrecting this dividing line between the Indigenous and the non-Indigenous, and that that line could only be crossed through miscegenation, blood mixing. It was shocking. I didn’t have to have any African ancestry, and yet, I thought of myself as a man from Africa. I was an African.

I remember Thabo Mbeki’s speech in parliament defining who is an African. And I remember Afrikaner politicians standing up, one after another, each one saying, “I’m an African.” “I’m an African.” That was the fruit of the anti-apartheid struggle. The Times was so narrowly preoccupied with marginalizing one candidate that it seemed to have forgotten everything else.

You wrote in the book that despite having been raised in a pretty segregated society in Kampala that your political awakening occurred in the US. What was it that you saw in the US that changed how you understood where you had come from?

The big highlight was the civil rights movement and my going to the south, to the march on Montgomery. Then the anti-Vietnam war movement, and indirectly, through my girlfriends, the feminist movement. It was not an individual experience. There was a cultural revolution happening in the US. There was a wholly different mindset which was being born. Everybody I knew, more or less, shared this anti-racist orientation.

When I went to Dar es Salaam, I was involved in an intellectual environment which gave me reasons for understanding this transformation and informed me of the larger anti-colonial movement, beginning with the Russian Revolution and the Chinese Revolution, the Vietnam Revolution, the Cuban Revolution.

Today in New York – the New York experience keeps changing, and now with the election of my son as mayor, it’s changing even more. The sense of possibilities is broadening. I was quite surprised to see Zohran embrace where he came from openly and directly. “I’m a Muslim. I was born in Africa. I’m of south Asian descent,” and so on and so forth. New York continues to be a lived experience.

At the same time we are seeing calls on the national level for mass deportation and efforts to carry out the expulsion of disfavored groups from the US. Do you see parallels with the expulsion of Uganda’s Asians?

All the threads which led to the Asian expulsion in 1972 and, before that, the expulsion of the Luo [people], are present in the US now: birthright citizenship, Indigeneity. There are resonances, even similarities, but they’re not the same.

The big difference, I think, is that there is a counterthrust here, and it’s just beginning. I think this election in New York City is a possible beginning. I don’t want to be too optimistic, but it’s a possible beginning because it’s had resonances, not just throughout the country, but even outside the country.

Can you say a little bit more about that? My perception of Zohran’s campaign was that he spoke about universal values even as he celebrated in a very specific way his own identity and the identities of his supporters. It was a very different kind of politics than what we get from the Democratic party these days, which often seems to shy away from openly embracing immigrants or Muslims.

I understand the contemporary situation in the US as being a product of decades-long encounters, which we call cultural wars, that were played out in the academy, in the intelligentsia. The key cultural war was around the notion of affirmative action. Should affirmative action be a temporary phase, or should it be a permanent phase? If it becomes a permanent phase, does not the quest of justice turn into revenge? Are you not holding children responsible for the deeds of their ancestors? If the children are going to be beneficiaries of the deeds of their ancestors, do they carry a measure of responsibility? I don’t think there is any clear-sightedness on whether affirmative action in the US should be permanent or not, but it’s a big issue, and it’s now coming to the fore.

One of the ideas in the book that I was drawn to was the idea of federation – a system that “bases the notion of political belonging on where one lives rather than where one comes from”.

My first encounter with the notion of federation was in the thinking of Abraham Lincoln and the amendments which changed the notion of citizenship. Before the civil war, you were a citizen of the state in which you were born. After the Civil war, you could be born in Alabama and move to California, and you would have the same rights as somebody born in California. This federal arrangement – a common citizenship, but not a centralized order – is under threat now. Both parts of it are under threat. Common citizenship is under threat and a federated [non-centralized] order is under threat, with Trump occupying cities with the national guard.

In the African context, federation was always seen as a colonial maneuver. Federation was a name for emasculating the newly born independent governments and for empowering erstwhile privileged groups. But now federation is increasingly being embraced as part of an agenda against authoritarian regimes, dictatorial regimes, regimes like Musaveni’s.

One theme of the book is how neoliberalism challenged and damaged Uganda’s university. How would you compare what happened there with the turmoil at Columbia in recent years? What do you make of the school’s capitulation to the Trump administration?

There’s a definite connection. On the surface – not just superficially, but immediately – it is seen as an ideological confrontation, not as a confrontation about the structure of the university. But the background to 7 October 2023 and Minouche [Shafik’s] administration at Columbia was the [Lee] Bollinger era [from 2002 to 2023]. Bollinger brought about structural changes at Columbia. By the end of it, we got a bloated bureaucracy at the heart of which was the financial bureaucracy. That bureaucracy understood Colombia as a business enterprise with pluses and minuses, gains and losses. It was not really interested in Colombia as an academic institution.

Minouche was brought here from the World Bank to [lead] that bureaucracy. She had no understanding of American academia. She had no experience in a large university. Poor Minouche comes and finds herself facing an encampment for which she was completely ill prepared.

At the time we were blaming Minouche as the central character in what happened here. I now think that her lack of experience, her ignorance, was taken advantage of by others. She was more or less locked up in her office, and she resigned as an honorable way out, in a sense.

She’s like an Idi Amin character; I’m trying to understand her. I’m not apologizing for her. If you print this, the Wall Street Journal will come back.

Are you planning to return to campus to teach, given the systems that have been put in place to police the academic content of scholarship at Columbia?

I’m definitely planning to come back and teach. I want to be involved in the kind of future we craft. I’m not willing to give up now.

You were asked by Museveni to take an active role in his government on multiple occasions and declined. I was looking at the hardcover of Slow Poison last night and realized that you had added a final paragraph that wasn’t in the galley that addresses some of the complications that arise when intellectuals interact with power – the potential for corruption, the desire for “clean hands”. You end on an ambiguous note: “For now at least, we explore for an answer in the realm of practice.”

Your son is going to be in power in New York City. Are you interested in playing a role in or influencing his administration?

We have been very close as a family: Mira, Zohran and I. This book would have been like one of my other books, which is me standing at a distance and narrating what happened to others, not to me, but both Zohran and Mira kept telling me: “You have to insert yourself as a character in this. You were alive. You were involved. Take responsibility, but tell us. Tell us the part of the story which nobody else will be able to tell us.” So different versions of the book insert me more and more and compel me to understand the difference between the claim to objectivity and an understanding of positionality – that you are a limited witness who is looking at events from a particular vantage point, and that vantage point is both your strength and colors you.

That ambiguity is an admission that I haven’t found an answer to the question. I don’t believe one should just stay away from power, but I don’t think we should embrace it. Power is a fatal thing for intellectuals. It corrupts intellectuals. I’ve seen many, many, many a friend get corrupted in the process.

As to how I will relate to Zohran’s administration: I think initially at least both Mira and I will have the relationship we did during the campaign, which is to stay at an arm’s length but always be available. Always be available for discussion, for sharing our point of view, but not mistaking ourselves for being him.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  3 hours ago

3 hours ago

Comments