For the first time in more than half a century, there are no binding restraints on the buildup of the largest nuclear forces on Earth. The New START treaty expired on Feb. 5, 2026, ending the last agreed limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

New START limited the number of strategic nuclear weapons the United States and Russia could deploy to 1,550 each. It also limited the missiles and bombers those warheads were loaded on, required on-site inspections and data exchanges, barred interference with satellite monitoring, and established a joint commission to discuss disputes. It did not limit the number of nuclear weapons each side could hold in reserve.

With China rapidly building up its nuclear forces, intense rivalry between the United States, China and Russia, and evolving technologies – from precision conventional weapons to artificial intelligence complicating nuclear balances – there is a real potential of an unpredictable three-way nuclear arms competition.

Such a competition could increase the danger of nuclear conflict, which I believe is higher than it has been in decades.

The security of agreed restraint

While the particular numbers of warheads and delivery vehicles an accord specifies may not make an immense difference, nuclear agreements offer important advantages in four key areas:

Predictability, limiting the pressures to build up nuclear arsenals that come from worst-case analysis of what adversaries might build and the destabilization that unexpected new weapons can bring.

Transparency, elements such as data exchanges, on-site inspections and limits on interfering with satellite monitoring, giving each side a better ability to understand what is going on with the others’ nuclear forces.

Reduced first-strike incentives, from banning or limiting particularly dangerous types of weapons.

Improved relations, through the mere fact that the other side is willing to limit the nuclear forces arrayed against you, which undermines the belief that they are implacably bent on your utter destruction. This reduces the intensity of hostility that can drive crises and escalation.

After 1962’s Cuban missile crisis, President John F. Kennedy realized that relying on nuclear deterrence without any agreed nuclear restraints or risk-reduction measures is just too dangerous. He moved quickly to negotiate the Limited Test Ban Treaty in 1963 and put in place a U.S.-Soviet hotline for crisis communication.

He also launched a series of initiatives that led to reductions in defense spending on both sides, cuts in production of nuclear materials for weapons, and even troop pullbacks in Europe. Every subsequent U.S. president has pursued nuclear arms control accords.

Moreover, the countries that have promised not to get nuclear weapons under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty want to see the nuclear-armed nations living up to their treaty obligation to negotiate in good faith toward nuclear disarmament. As pressure builds for countries to get their own nuclear weapons, maintaining the nonproliferation regime and getting the non-nuclear countries’ votes for stronger nuclear safeguards or export controls is likely to require the nuclear-armed nations to accept at least some constraints of their own.

Critics of arms control point out that Russia has violated many past accords – and the Trump administration has accused both Russia and China of carrying out illicit nuclear tests, though his administration has not offered solid evidence in public so far. But despite these very real issues, key elements of these agreements were implemented, and they “left the United States safer,” as Secretary of State Marco Rubio has noted. More than four-fifths of the nuclear weapons that used to exist in the world have been dismantled.

New limits or buildup?

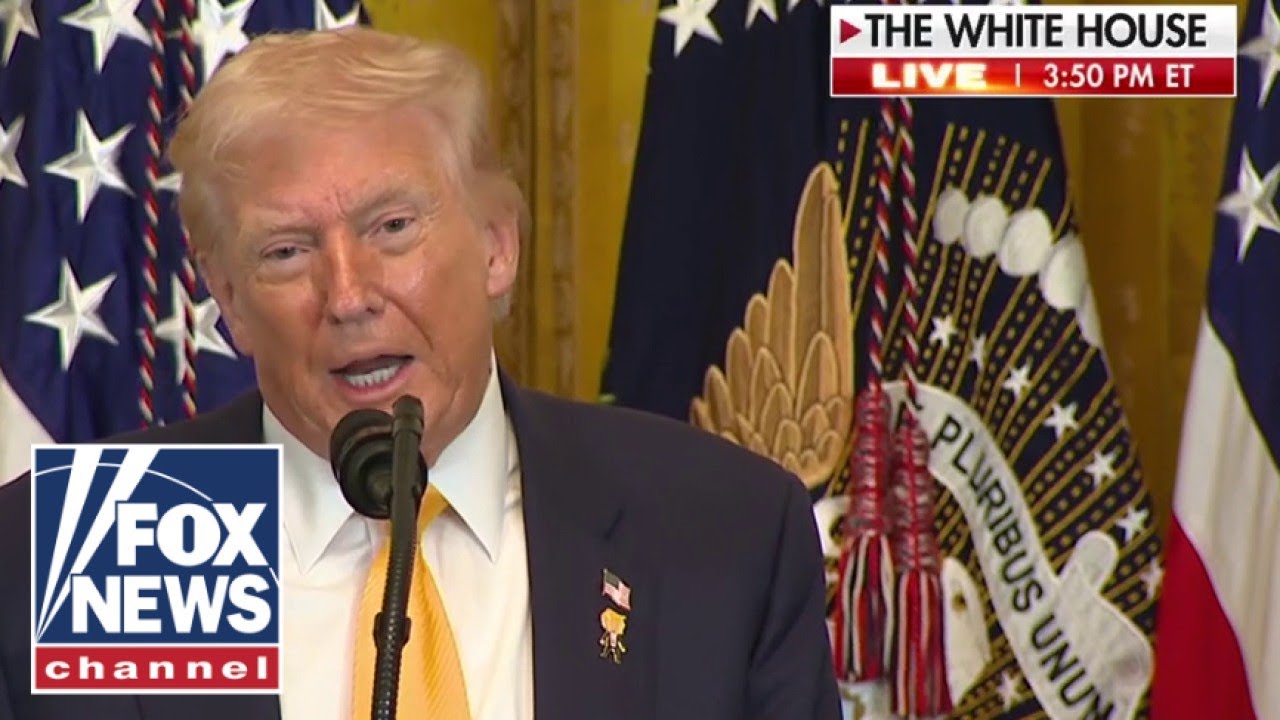

So, what’s next? President Donald Trump ignored Russian President Vladimir Putin’s proposal that both sides stay within the limits of New START while they explored options for new steps. But Trump said he wants to negotiate a “better” deal on fewer nuclear weapons – a deal that would not only limit U.S. and Russian strategic forces but also China’s much smaller but rapidly growing nuclear forces and Russia’s large force of nonstrategic nuclear weapons – that is, ones for battlefield or regional use.

So far, though, no negotiations on follow-on accords are underway, and the administration has not offered to negotiate about any of the U.S. weapons systems that worry Russia and China.

Moreover, there is strong pressure in Washington to build up U.S. nuclear forces rather than reduce them, to deter both Russia and China – while also dealing with the smaller but still dangerous North Korean nuclear force. The United States has many hundreds of nuclear weapons in storage that could be brought out and put on existing missiles, along with empty missile tubes on submarines that could again be filled with missiles. And the U.S. is developing new weapons, such as a nuclear-armed, sea-launched cruise missile.

Constraints and challenges

In my view, the more than 1,500 strategic nuclear weapons the United States already has deployed – with a major modernization underway – provide a sufficient deterrent to aggression. And if the United States begins to build up, Russia will respond in kind, and China may go even further. Once a multisided buildup is underway, its momentum will be more difficult to reverse.

Fortunately, the United States, Russia and China all have strong national interests in avoiding an unrestrained nuclear race, which would leave all of them poorer and no more secure. While the United States has quite a few nuclear weapons in storage, its nuclear modernization is struggling with enormous delays and cost overruns, and its industrial base is simply not prepared for a major nuclear expansion.

Putin is building a war economy that can churn out a lot of weapons – but he knows his economy is a 10th the size of the U.S.’s, and he wants to focus on rebuilding the conventional forces being chewed up in his war on Ukraine, making nuclear competition a bad idea. China has an economy to match the U.S.’s and an unrivaled manufacturing capacity, but it, too, would be worse off if its buildup provokes a U.S. buildup in response and a collapse of nuclear restraints.

Despite these common interests, finding a path to new accords among at least three parties, rather than two, will not be easy. Coalitions in each capital will have to win arguments that an accord is in their nation’s interest at the same time. The parties will have to address in some way the non-nuclear technologies that affect nuclear balances, and technologies such as cyber weapons and artificial intelligence would be hard to count or verify.

U.S. political polarization might make it very difficult to get a two-thirds vote in the Senate to ratify a treaty – though there are many other possible approaches, from reciprocal political commitments to executive agreements.

Famously unpredictable, Trump might still reverse course and agree to some version of Putin’s proposal for a “strategic pause” in which neither the United States nor Russia would build up its nuclear capabilities for the time being, while talks on next steps were underway. That would have the advantage of offering time to explore the options before new nuclear buildups got locked in.

And that would give him more chance of reaching his oft-stated goal of being the one to bring home a deal to reduce nuclear weapons and the dangers they pose.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  8 hours ago

8 hours ago

Comments