Modern weather forecasts have never been so accurate, but they still have their limits.

The intense rainfall that sent floodwaters coursing through central Texas last week and surprised even some Texas officials with the severity has brought into stark focus the challenge of forecasting the most severe storms and what even the best weather models can’t deliver.

“There’s an expectation a catastrophe like this is going to be able to be forecast hours or days in advance and that’s just not the case,” said Alan Gerard, a former director of the analysis and understanding branch at the National Severe Storms Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Models “can basically show there will be areas of intense rainfall, but they very rarely put it in the exact right spot.”

Efforts to close that rift are at risk. Climate change is increasing the frequency of extreme rainfalls, making improvements to models all the more urgent. NOAA is working to improve forecasting tools to better predict rainfall intensity and precise location, but the Trump administration’s most recent budget request for the agency, which proposes to cut the budget by more than $2 billion, would shut down much of the agency’s severe storm research.

While National Weather Service forecasters had warned broadly about flash flooding in central Texas in advance, Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon said the best weather models could not predict precisely where the most intense rainfall would fall, or that the deluge would stall out over a flood-prone basin.

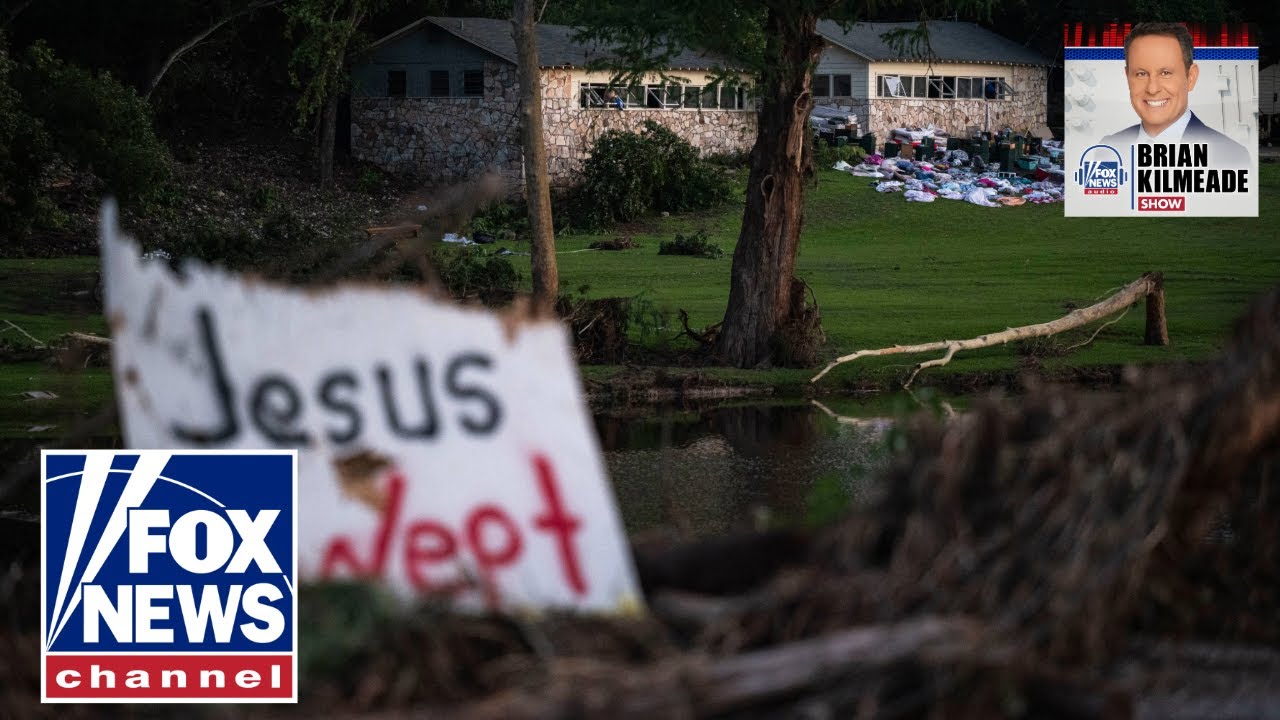

Debris lies along the Guadalupe River in Ingram, Texas, on Tuesday. (Jim Vondruska / Getty Images)

“It would have been next to impossible with present-day technology to get the internal dynamics of the storm right,” Nielsen-Gammon said, which is key to determining whether a storm will stall out as it did. In this case, Nielsen-Gammon said 3 to 4 inches were on the ground before it was apparent the system was stalling and would produce such intense flooding over the south fork of the Guadalupe River, where the most intense destruction ultimately occurred.

“If you look at the radar map, at say 1 a.m., there was stuff all over the place,” Nielsen-Gammon said of the region’s scattered storms. “You would not have singled out Kerr County.”

NOAA and its academic partners are working to develop better tools to predict flash flooding. David Gagne, a National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist who is focused on using machine learning to improve weather models, is developing artificial intelligence algorithms to improve short-term forecast accuracy, for example.

Gagne said NOAA has already developed another tool designed to increase the lead time for flash flooding called the warn-on forecast system, but it is not yet operational for forecasters with the National Weather Service.

The Trump administration’s budget request for NOAA in fiscal year 2026 would nix the warn-on forecast system and the agency’s research labs, which drive forecasting innovation.

“All of NOAA research would be eliminated with a few small programmatic exceptions. All of this work to improve the various forecast warnings within NOAA would pretty much end,” Gerard said.

Damage at an RV park in Center Point, Texas, on Monday. (Ashley Landis / AP)

Right now, the best tools available can provide ample warning of a general flash flooding threat, but localized flash flooding can only be predicted when real-time radar and sensor tools are able to determine the rainfall rates.

“The reality is for flash flooding in flood-prone areas, you should be thinking about it in the same way you do a tornado,” Gerard said. “We can’t tell you your particular spot is going to get hit in the same way we can’t tell you your particular spot is going to get hit by a tornado.”

Scientists expect more intense rainfall events as human use of fossil fuels warms the atmosphere, making the quality of weather models even more important.

For every degree of warming in Fahrenheit, the atmosphere can hold about 3% to 4% more moisture. Global temperatures in 2024 were about 2.32 degrees higher than the 20th-century average, according to NOAA data.

“Rain occurs when you have a really moist parcel of air at the surface and it rises in the atmosphere and it cools off … think of a sponge full of water and you start squeezing, wringing out the sponge and the water falls out,” Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University, said. “In a warmer atmosphere, there’s more water in the sponge, so when you wring it out, you get more water falling.”

While climate change increases the odds of extreme rainfall, it shouldn’t have effects on the accuracy of weather models because they rely on real-time weather observations and the basic, underlying physics that govern interactions between all kinds of matter. The laws of physics are impervious to climate change.

“They’re using input data that has climate change in it,” Dessler said. “It’s incorporated.”

In Texas, higher temperatures have already translated into more intense rainfall. In a 2024 report, Nielsen-Gammon found that “extreme one-day precipitation” had increased by 5% to 15% since the late 20th century. By 2036, he expected an additional increase of about 10% in extreme rainfall intensity.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  21 hours ago

21 hours ago

Comments