The government shutdown may have prevented the publication of September’s job report, but we can be reasonably confident that when the numbers are known, they will further underscore the Trump administration’s policy incoherence and remind us of all of the damage he is prepared to inflict on the American economy.

The president will most likely be apoplectic over data confirming that the economy is generating very few new jobs (the payroll processor ADP estimated a loss of 32,000 private sector jobs in September). Trump fired the head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which produces the jobs numbers, after a lackluster report published in August.

But in the office of his deputy chief of staff, Stephen Miller, champagne is likely to flow. For Miller, the dismal job growth is largely due to the war against immigrants he has masterminded from his perch on the White House’s second floor.

The cognitive disconnect ultimately stems from a stubborn misrepresentation preached across the administration about the impact of immigrants on the American economy: that every immigrant expelled from the workforce frees up a job to be readily filled by an unemployed American. In Miller’s words: “Mass deportation will be a labor-market disruption celebrated by American workers, who will now be offered higher wages with better benefits to fill these jobs.”

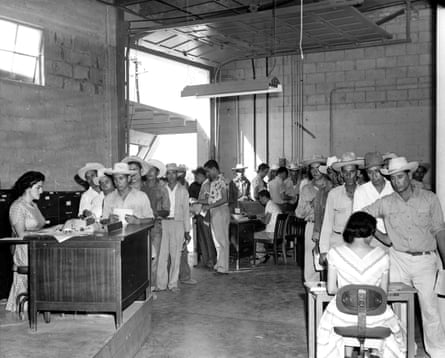

Photograph: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

This is what inspired the agriculture secretary to propose that farmers who lost their workforce to an Ice raid should have their crops picked by Medicaid recipients who need a job to keep their benefits. It explains JD Vance’s smug mood in August when a government report suggested, implausibly, that there had been a momentous decline in the immigrant workforce and a corresponding increase in the number of Americans with a job, a pattern that turned out to be a statistical mirage.

As economists repeatedly try to explain to the likes of Vance and Miller, the economy doesn’t work like that. A newly deported migrant does not yield an employed native. Indeed, the deportation is likely to cause employers to let go of American workers too. What deportations do achieve is to reduce the labor force. The native-born workforce shrank last year. Hiring is slow largely because kicking migrants out means there are fewer workers to hire.

At the end of the day, the White House’s attempts to rid the labor market of immigrant workers will cripple American prosperity – damaging industries that rely on immigrant labor, from agriculture to hospitality and eldercare to healthcare. Businesses will shrink and even go under, punishing the American workers who toil alongside the foreign-born. American history keeps teaching us the same lesson: the prosperity of this land relies on immigrant work. Somebody let Trump know.

Consider the previous attempt at mass deportation. About 424,000 undocumented immigrants were “removed” from 2010 to 2015 under the “Secure Communities” program during the administration of Barack Obama. Studying the impact on the workplace as the program was implemented county by county over four years, economists from the University of Colorado estimated that the 3.5% fall in the employment of immigrants as Secure Communities rolled out was associated with a 0.5% decline in the employment of citizens.

A few decades prior, the end of the “Bracero” program in December of 1964 excluded almost half a million Mexican seasonal farm workers, who had been coming to plant and harvest crops since the 1940s. According to another study, the demise of the Bracero program did nothing to raise the employment or wages of native farm workers. Farmers who could, mostly those growing tomato, beet and cotton, mechanized production. But they didn’t pay more.

Nor did the mass “repatriations” of hundreds of Mexican immigrants and their US-born children during the Great Depression improve the lot of American workers. Rather, economists found that the employment and wages of native workers declined in the most affected counties.

On the flipside of this dynamic, economists studying immigration over the first two decades of this century found that the inflow raised the wages of less educated native workers, those with at most a high school diploma. Their conclusions resemble those of studies of the immigration wave of the early 20th century that found it spurred industrial production and increased native employment. Native workers left immigrant-heavy jobs – manual laborers, waiters, blacksmiths and the like – and took higher-wage positions as foremen, electricians or engineers.

After Congress passed the nation’s first-ever national immigration quotas in the 1920s, driving immigration down over the coming four decades, businesses in affected areas responded in a variety of ways – drawing workers from other states and other countries, introducing labor-saving technology or reducing production. The impact on native workers was, at best, ambiguous.

These outcomes are not hard to comprehend. Whatever Trump, Miller and co are trying to spin, understanding the impact of immigration requires looking at its impact on businesses, which will invest to profit from the additional labor, as well as on the occupational decisions of native workers, who will move to better jobs out of immigrants’ reach.

Barring immigrants from the economy will reverberate beyond the labor market. Just like during the second world war, when the exclusion of Japanese farm workers slashed agricultural productivity and output by pushing the most productive farmers off the fields, kicking out foreign graduates will strain America’s pool of skilled workers and limit the number of startups. Limiting H-1B visas won’t create more jobs for citizens but trim employment, sales and profits in technology firms.

It is true that immigration is politically unpopular. While Trump’s draconian treatment of immigrants and their communities might strike many as inhumane, many Americans have come to believe immigration amounts to a problem rather than an opportunity.

This would not be the first time in history that this nation of immigrants turns against its most defining feature. It is, however, a perilous moment to do so. As the population ages and the domestic labor force shrinks, political leaders now claiming a mandate to rid the nation of its foreign labor force may be summoned to account for the consequences.

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  4 hours ago

4 hours ago

Comments