When Shawn Pleasants first heard that the federal government was tearing up almost two decades of homelessness policy, it sent chills up his spine.

Pleasants, 58, was brought right back to the moment he lost his car and was forced to start living on Los Angeles’s streets. “That feeling of, you could never be safe – there’s no more future,” he said.

He’d spend a decade living on the streets of Koreatown, until the day he and his husband received a section 8 voucher from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Continuum of Care (CoC) program.

Continuum of Care is the federal government’s flagship program to support state and local governments and non-profits in funding housing and other services for individuals, like Pleasants, at risk of or experiencing homelessness.

The program is built on the principle that getting unhoused people housed can get them on a path to address other challenges. It has worked for Pleasants, who has had an apartment for the past six years, and more than 100,000 other Americans.

But in the past months, the Trump administration has tried to issue sweeping policy shifts to the program, some of which shifts it has since reversed, others of which have been temporarily halted by the courts. The chaos has sown widespread confusion among local governments, providers and people unsure whether they will face eviction in the winter months.

“It has been a massively chaotic and disruptive moment for our organization and all of the local governments and non-profit homeless service providers that we partner with,” said Amanda Wehrman, the director of strategy and evaluation at Homebase, a non-profit that provides technical assistance to many CoCs.“It’s been really chaotic both in terms of the stops and starts, the uncertainty about funding, the inability to think strategically about what comes next.”

The first changes came in November, when HUD announced it was redirecting the majority of federal housing vouchers away from permanent housing to funding for temporary shelters. Jurisdictions applying for a piece of the $4bn in annual federal homelessness funds would only be able to spend 30% of their grants on permanent housing, down from around 90%.

This shift could leave 117,000 people nationwide without supportive housing and put them back on the streets, according to internal HUD documents obtained by Politico.

“Housing-first is clearly not working in California or the rest of the country,” HUD spokesperson Matthew J Maley said in an email at the time, adding that “HUD is stopping the Biden-era slush fund”.

The new policy also mandated treatment for recipients, and penalized jurisdictions that employed harm-reduction strategies such as safe consumption sites or that recognized transgender or gender-diverse people – groups that disproportionately experience homelessness.

The administration rolled back those restrictions in December, shortly before a federal judge was to hear two lawsuits on the issue. Later in the month, several court orders temporarily blocked the funding overhauls, ordering HUD to process projects for 2025, though stopping short of compelling the administration to award the funds.

HUD issued new guidance in January in response to the court order, with CoC funds auto-renewing and a 9 February deadline for projects needing to be updated, though no funds will be awarded until the case is resolved.

In an email to the Guardian in January, Maley said that “HUD will respect and adhere to current judicial directives ordering the reinstatement of the 2024 2025 NOFO while reserving all rights to appeal”.

“HUD fully stands by our objective to overhaul America’s failed homelessness system, which has relied almost exclusively on permanently warehousing the homeless at exorbitant taxpayer cost while ignoring root causes,” HUD said in an email.

HUD did not respond to questionsabout evidence behind the assertion that housing-first policies were not working, were wasteful or were ignoring the root causes of the homelessness crisis.

Housing first

Housing first has been a bipartisan policy since George W Bush, and was codified into federal law by Congress in 2009. It is considered to be evidence-based by experts who spoke to the Guardian.

Housing first was a game-changer for getting people treatment by first getting them permanent supportive housing, said Dr Margot Kushel, a physician and the director of the Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative at UCSF. She has been treating people since before the housing-first strategy. To throw out this strategy would be “just silly, counterintuitive and dangerous”, she said.

Kushel conducted the most comprehensive study yet of homelessness in California and is emphatic that the cause of homelessness is a lack of housing. “Our minimum wage, our fixed income – whether it be retirement, disability, social security – none of them have kept up with the cost of living. People can’t work 150 hours a week,” she said.

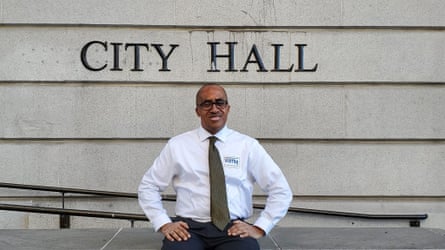

Pleasants, a valedictorian who studied economics at Yale and worked on Wall Street, said he fell into homelessness after a business conflict overlapped with the death of his mother, leaving him emotionally and financially ruined. Through the kindness of strangers and help paying for his apartment from HUD, Pleasants got his life back together and now advocates for others through the Lived Experience Advisory Board of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (Lahsa).

He has many questions about how jurisdictions will triage who loses their homes or not if the funding changes would become permanent: “Are they going to choose the ones they want to terminate randomly? Are they going to do it to the oldest ones, or the newest ones, or are they going to choose acuity?”

Pleasants loves cooking his mother’s Creole recipes and eating on real plates with silverware – simple pleasures that are nearly impossible when sleeping rough or living in a tent. He fears he could be on the list of those slated for eviction should funding end, but isn’t sure how he should raise the alarm to others at risk, given the uncertainty of where the funding stands.

“I can’t think of anything more damaging than to take people that are on the path to having their lives under control again and place them back on the street,” said Pleasants. “I don’t know if I’ll be able to do the work that I do from the street, from my laptop out of a tent.”

Many jurisdictions ran out of Continuum of Care funding in January, and many other grants are set to expire in the first quarter of 2026. Even without the lawsuits and confusion around funding, many HUD grants wouldn’t be approved until late spring, leaving jurisdictions to scramble to fill the funding gap or take a gamble not knowing if money will come through.

Jonathan Russell, director of Alameda county health’s housing and homelessness services, oversees the county’s application for Continuum of Care funding, which includes 47 grants totaling about $60m.

Russell spent much of November and December scrambling to find local funding to replace the $33m shortfall and mitigate the impacts of what he described as a “tide change” in HUD funding being implemented “overnight”.

Roughly 85% of HUD’s CoC funds to Alameda county go towards permanent supportive housing for people who have experienced long-term and chronic homelessness. People with “complex conditions, disabling conditions, kind of the most vulnerable folks in our communities”, Russell said.

He fears HUD’s policy changes will significantly increase homelessness, costs to local communities, and the suffering of the county’s most vulnerable residents.

Russell disputes the idea that housing-first policy doesn’t work, arguing that, if anything, the investment doesn’t match the scale of the need: “Blaming housing first for not solving homelessness is like blaming alternative energies for failing to mitigate climate change when it’s actually just the scale at which we’ve done it that’s the problem.”

Paying for permanent housing for people with complex needs is significantly more cost-effective than paying for them to stay in shelters or on the streets, said Russell.

In California, permanent supportive housing costs an average of $20,000 to $25,000 per person per year, while a shelter bed can cost $40,000 to $50,000 annually, said Russell.

“Studies have shown it can cost between $75,000 to $80,000 per year” to treat someone with complex needs while they remain on the street, said Russell, a cost typically driven by reliance on “emergency services, first responders, emergency departments”.

Russell said he sees the housing-first strategy, with wraparound services for the most vulnerable, work every day, with a retention rate among those who’ve been housed at 80-90%.

Shelters, on the other hand, overwhelmingly see people exit back onto the street or to unknown locations, with only about 15% of people moving from them into permanent housing – the ultimate measure of success – according to a California statewide assessment.

Angel Smith, whom the Guardian is identifying through a pseudonym because she fears being denied housing or services for publicizing her experience in the system, said she’s struggled with housing instability since the 2008 economic crash. To escape an abusive housing arrangement, Smith, 61, jumped through the many administrative hoops necessary to be admitted into a Marin county homeless shelter last fall. She found the food adequate and made some friends, but checked herself out after three weeks because she couldn’t ever get more than two hours of uninterrupted sleep in the shared dorm room.

“I snore, so keep others up. Then, one girl, she’s on her phone freaking all night. The other girl, she wakes up, like clack, clack, clack. Then, the guards come and wake you up every two hours,” said Smith, an environmental, art and outdoor educator.

The sound of the guards unlocking the door, saying “bed check”, then shining a flashlight onto everyone’s bed to make sure they were still there felt like “prison”, given there were 24/7 surveillance cameras in the hallways. The lack of sleep, the rigid curfew and restrictive parking was all more than she could take while trying to hold her teaching job. She’s gone back to her previous house and is waiting to be evicted.

Smith said that if HUD defunds permanent housing, the DMV should allow cars to be designated as homes.

For Pleasants, one of the most soul-crushing things about living on the streets was having to hold makeshift funerals for people who didn’t survive:

“People die on the street. Not only do they die, but they die unremembered. They’re separated from their friends and family. The city just wants to dispose of the body. They don’t want to hold a service. All the things that we normally do in life are removed, and we try our best to have ceremonies in the back of the library, light a few candles and share stories of the person.”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 hours ago

2 hours ago

Comments