In the hours after the 7 January fatal shooting of Renee Nicole Good, a 37-year-old Minneapolis mother of three, gut-wrenching footage of her killing was released, discrediting initial claims from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents and the Department of Justice that she was shot in self-defense. As a response to the public outcry, the Trump administration and a chorus of conservative public figures unleashed a litany of dehumanizing and defamatory remarks about Good, a beloved wife, neighbor and dental assistant, in ways that were unduly callous.

The Fox News host Jesse Watters derided Good’s queer identity, and mocked her as a “self-proclaimed poet from Colorado with pronouns in her bio”. The homeland security secretary Kristi Noem vilified Good as a domestic terrorist who “weaponized” her vehicle in an attempt to run over officers – a patently false comment. Laura Loomer, a personal adviser to the president, posted to social media, “She deserved it … I’m shocked her lesbian girlfriend wasn’t shot with her.” JD Vance lobbed the biting accusation that the victim was “a deranged leftist”, before adding that “it’s a tragedy of her own making”. Donald Trump justified the shooting, telling reporters that “at a very minimum, that woman was very, very disrespectful to law enforcement”. And on 17 January, the justice department announced a criminal investigation into claims tying her grieving widow, Becca Good, to unnamed “activist groups” (six federal prosecutors resigned in objection to the investigation).

In the past month, much of the public has been in disbelief as they’ve grappled with ICE’s relentless violence. “You felt like your stomach was being punched,” the Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer said of watching the video of Good’s killing. It has forced into focus a realization of just who this administration will sacrifice in pursuit of its targeted populations. Good’s death has managed to achieve something that the state’s quotidian deadly force against Black and brown communities has not: it has laid bare the tenuous relationship between white womanhood and white supremacy.

That Good was killed while going about her daily routine is not at all shocking to those of us who experience state violence as part of our day-to-day lives. What shocked so many people of color was witnessing law enforcement target and execute a white woman – an almost consecrated category in the American conscience of rightful victimhood. The idea that government agents can harm a white woman with impunity is an affront to our national sensibility.

White women’s victimhood holds sacred status in the mainstream American imagination. Cowboy westerns where white women were rescued from “savage” Natives spun the genocidal project of “manifest destiny” into a classic image. Across film and television, setting the scene for the dangers of inner cities relies on cliched encounters between young Black male street “criminals” and the lone unassuming white woman who is terrorized by them while walking at night. These made-for-TV mythologies are a bulwark of pro-law enforcement propaganda. Because of that, the right’s excessive assault on Good’s life and legacy was almost required. White supremacy demands that even white women be vilified if their deaths challenge the narrative that the government’s brute force is always deployed in the interest of whiteness. The state-backed messaging that Good was the wrong kind of white woman, therefore, was a foregone conclusion.

Good did not properly defer to the white male authority of armed agents occupying her neighborhood, nor was she adequately afraid of living in a multiracial inner city. (She was stopped by ICE just blocks away from the intersection where a Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd.) Worse, Good was insufficiently grateful for the masked men in tactical gear sent there to defend her from Somali immigrant bogeymen. State violence wielded as protection for white women has long been a touchstone of white racial domination. The circumstances of Good’s death, then, complicate – and at worst, invalidate – that narrative.

In every epoch of the American project, the expansion of white state power, the justification of land theft, and the exploitation of Black and brown people have been given moral cover with stories about defending white women against the threat of outsiders. That narrative is foundational to the righteous tinting of white supremacist violence, and a decisive reason why the assault on Good’s character was so swift after her killing by the state. But long before this messaging about white women’s need for protection was hammered by Fox News talking heads and far-right streamers, more than a century ago, this propaganda was fueled by the silver screen. One of Hollywood’s most celebrated sagas – the blockbuster film that made white America fall in love with the movies – was the basis for this enduring racist iconography.

The birth of a racial myth

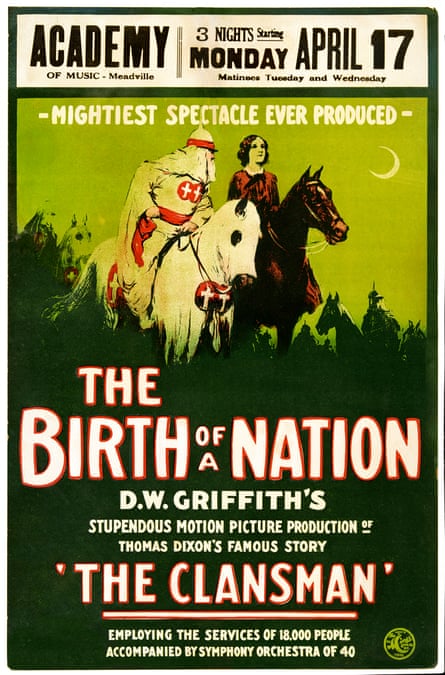

In 1915, white moviegoers in Minneapolis and hundreds of other US cities queued for blocks, having paid an unprecedented $2 for the theatrical release of Birth of a Nation. The Confederate-sympathizing silent drama was as much a landmark for cinematic innovation as it was for reigniting a reign of racial terror across the country. The picture fictionalized the outcome of the civil war to suggest what would have happened if the newly freed Black population seized government control of the reunited states. Based on the novel The Clansman by Thomas Dixon, a former college roommate of then sitting president Woodrow Wilson, and directed by DW Griffith, the film laments the loss of what it deems the bygone halcyon days of slavery by dramatizing the horror and chaos of a country that allows Black participation in American democracy.

In this film’s alternate depiction of Reconstruction – the short-lived period between 1865 and 1877, in which Black freedmen were elected in record numbers to local, state and national office (including 16 Black members of Congress) – the federal government is overrun by rapacious, ravenous and uninhibited Black men. Portrayed in minstrel blackface by white actors, their political and social gains are motivated solely by their marauding lust for white women. The only white women featured as principals are daughters of a southern slaver family, and their character arcs are wholly motivated by their efforts to resist Black men’s sexual advances. In a culminating action sequence, one of the sisters jumps to her death rather than having her virtue sullied by the Black predator giving chase. The scene flashes to an intertitle that reads: “For her who had learned the stern lesson of honor … we should not grieve that she found sweeter the opal gates of death.”

For this mortal act, she is revered for her uncompromising devotion to preserving white racial purity. She is a hallowed victim because she died upholding her feminine obligation to remain the property of white manhood. Her fictitious martyrdom ignited the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan both on and off screen (the film was used for Klan recruitment for decades). The group’s domestic terror campaign against a multiracial democracy was immediately rebranded as a white men’s chivalrous cause to restore racial order. Those 13 years of Black social and political progress during Reconstruction were, in reality, followed swiftly by a “nadir” period, which removed Black officials from office. Union troops were withdrawn from the south and unchecked former Confederates sought murderous vengeance on the thriving freedmen they once called property. The Klan’s charge then was to safeguard white women against the threat of Black political power – power that was considered nothing more than a ruse for Black men to pillage white men’s sexual property for themselves.

Birth of a Nation’s three-hour runtime is driven by a simplistic message that Black political power is a peril to white womanhood, and that white women are “virtuous” and “unblemished” so long as they are loyal to white masculinity. The presumed innocence of white femininity has served as the necessary political foil to the criminality of Black citizens and now, as we are seeing today, racialized immigrants.

For the right, the killings of people like George Floyd by a police officer, or Keith Porter Jr by an off-duty ICE agent, needed only be justified by the victims’ Blackness, as they were assumed to be inherently delinquent. The justification of Good’s killing, on the other hand, requires a bit more cunning. The proper role of a white woman as a vector of racial purity is at the bedrock of the racial hierarchy. But narratives about threats to white womanhood are only as useful as white men are able to deploy them to harm and hegemonize others. Racial barbarity under the guise of protecting purity presupposes that respectable white femininity can be tarnished by even the appearance of sympathy for antiracist politics and communities of color. The far-right podcaster Matt Walsh demonstrated this succinctly when he wrote of Good: “This lesbian agitator gave her life to protect 68 IQ Somali scammers who couldn’t give less of a shit about her.”

Trump’s infamous 2015 election announcement recycled 1915’s fearmongering by casting southern border immigration as a sexual threat to American women (the women’s whiteness implied). “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he ranted to a crowd gathered at Trump Tower. “They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists” – a racist message he later doubled down upon even after his own consistently predatory behavior with white women came to light. The fact that gender violence against white women is overwhelmingly perpetrated by white men doesn’t dent this propaganda. White men’s violence against white women is treated as a hushed matter for the private domain – the subject of personal proclivities and choices beyond the concern of government agencies and public policy. Protectionism exists only where it can clobber the rights of those who threaten the white racial order; white men are entirely exempted from their own self-serving mythology about white women’s safety.

Birth of a Nation was the first film to ever be screened at the White House. Wilson stamped the film’s racist indoctrination with an official seal of approval and added a flare of patriotic duty to support and join the KKK, which, by 1926, had gone mainstream. Ultimately, Birth of a Nation and its terroristic aftermath were as much a threat for Black people to stay in their place as it was for white women to stay in theirs. If it feels like Maga is going overboard to tarnish Good’s image, it’s because they are – the smearing serves the dual purpose of a warning and an invitation to white women. There is no white supremacist state control without white women’s fidelity to it. As such, the right must simultaneously denigrate Good as unworthy of protection while reassuring other white women of the racial rewards of their political loyalty.

It is no coincidence that the 19th amendment was ratified just four years after Birth of a Nation debuted, a “Red Summer” year that set records for lynchings and white mob violence nationwide. After half a century of public activism for the right to vote, white suffragists took advantage of the film’s racist and sexually laden fearmongering to cajole white men to their cause. Even as they had entered the suffrage movement decades behind the early 19th-century Black female abolitionists who birthed it, delegations of white suffragettes repaid white men by working state-by-state to exclude Black women from the amendment’s protections. (In what was the original “kitchen table politics”, Black women’s enfranchisement directly challenged white women’s ability to exploit them for cheap domestic labor and child rearing).

Since the ratification of the 19th amendment, white women have consistently voted in step with white men, and since 1952 – with the exceptions of Lyndon Johnson and Bill Clinton – they have voted majority conservative. No “women’s bloc” has ever materialized for white voters. Without white women’s devotion, there would have been no conservatives in elected office for the last century.

The majority of white women consistently vote against securing pathways to citizenship for immigrants, even as their own path to full citizenship was granted to reinforce and multiply white control of the country in the face of Black civil rights progress and early 20th-century immigrant influxes. It was for the express purpose of outnumbering Black voters (particularly in the south), suppressing Black political representation, and maintaining white racial dominance that white women were ever allowed into the American electorate.

For the right, a white woman worth protecting is a white woman whose gender role supports white male dominance. Not only should the heroine in a white supremacist narrative be willing to sacrifice her life to sustain white men’s proprietorship of government, but she should just as rightly be condemned to death for betraying her contract to white men’s authority over herself and everyone else. By most estimates, Renee Good, a devout Christian and dutiful mother, checks the boxes for what Maga says white women should be, which is why they must kill her character. In their view, Good failed to hit her mark in a script: a scared white woman opposite an ICE agent cosplaying the hero saving her from the dangers of a city filled with others.

The racial mission at the core of state violence is uninterested in discerning the race of its individual victims, so long as it remains wholly concerned with serving the larger aims of a racial agenda and hierarchy. The fatal 25 January ICE shooting of Alex Pretti, a white 37-year old intensive care unit nurse in Minneapolis, received a similar treatment to Good, with homeland security adviser Stephen Miller labeling Pretti “a domestic terrorist who tried to assassinate law enforcement”.

In the eyes of a racist state, race and gender are indicators but not absolutes when deciding who gets to be a “good” victim. Pure white womanhood deemed as “victimized” and chivalrous white manhood as “heroic” have long provided a moralistic makeover to immoral violence. But as we have seen with Good, the rules are as fluid as they are frivolous.

-

Saida Grundy is an associate professor of sociology and African American studies at Boston University, and the author of Respectable: Politics and Paradox in Making the Morehouse Man

-

Spot illustrations by Mona Eing and Michael Meissner

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  2 hours ago

2 hours ago

Comments