The rain was pouring down in Texas in the early morning hours of 17 July 1987. James Moore, a reporter for a local NBC news station, was stationed in Austin when his editors called and told him to grab his camera operator and head to Kerrville, a Hill Country town about 100 miles (160km) away. They’d heard reports of flash flooding on the Guadalupe River.

“We just jumped in the car when it was still dark … we knew there were going to be problems based on how much rain there was,” Moore said. En route, he got another call over the radio that told him to head instead for the small hamlet of Comfort, just 15 miles from Kerrville.

“They said: ‘Hey, head up towards Comfort,’” Moore recalled. “‘Something’s happened.’”

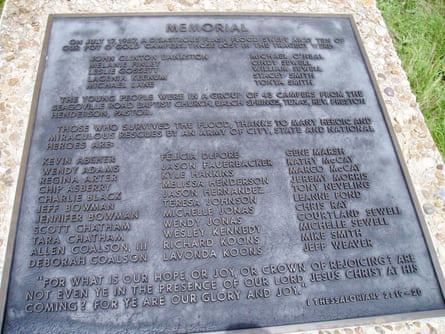

At about 7.45am, a caravan of buses had left a children’s church camp at the Pot O’ Gold Ranch as they tried to evacuate the Guadalupe’s surging waters, which eventually rose nearly 30ft (9 meters) during the ferocious, slow-moving rainstorm. According to a report by the National Weather Service, a bus and a van had stalled on an overflowing river crossing. As kids rushed to escape the vehicles, they were hit by a massive wave of water – estimated to be a half mile wide – that swept away 43 people. Thirty-three of them were rescued, but 10 children drowned.

Moore arrived at a scene of chaos. Helicopters clattered overhead as people scrambled in a frantic search for the injured and missing. Then he and his camera operator caught sight of something horrifying.

“We unfortunately found one of the bodies of the kids,” Moore said. “All we saw was the legs under a brush pile and we alerted the authorities.”

Nearly 40 years later, it felt like history repeating itself. Last week, in the early morning hours of 4 July, another flash flood hit the Guadalupe. This time, though, the wall of water was sizeably bigger, and came in the middle of the night and during one of the area’s busiest holiday weekends. The death toll is now nearly 130 people with more than 160 still missing. The loss of life includes 27 campers and counselors from Camp Mystic, a girls’ camp several miles upriver from Comfort.

For many who lived through the tragedy in Comfort, they see the 1987 flood as a harbinger for what washed through Hill Country on the Fourth of July.

“[The 1987 flood] was called the ‘big one’ back then. This is 100 times over what we experienced,” said Emily Davis. She was a 10-year-old at Camp Capers, another church camp up the road from the Pot O’ Gold Ranch, when the 1987 flood hit. “Why didn’t they learn from this? Why wasn’t there a better system?”

‘The risk is always there’

After the Independence Day floods devastated Kerr county last week, Donald Trump described the scene as “a 100-year catastrophe”.

“This was the thing that happened in seconds,” he added. “Nobody expected it.”

But Hill Country is no stranger to these disasters, and has even earned itself the moniker “flash flood alley”. Its chalky limestone cliffs, winding waterways and dry rocky landscape have made it ground zero for some of the deadliest flash floods nationwide. Hill Country’s proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and its ocean moisture have also made it a prime target for drenching thunderstorms.

The US Geological Survey calculates that the Guadalupe has experienced noteworthy flash floods almost every decade since the 1930s. In 1998, it recorded a flood that surpassed even 500-year flood projections. Other rivers in Hill Country, including the Pedernales and Blanco, have also seen deadly flash floods.

“What makes Kerr county so beautiful, the reason why people want to go there … is literally the reason why it’s so dangerous,” said Tom Di Liberto, a meteorologist who formerly worked at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa) and is now with the non-profit Climate Central. “The risk is always there.”

During the 1987 floods, as in 2025, news reports and video footage captured a harrowing scene: the Guadalupe’s surging muddy waters downing 100ft-tall cypress trees, as dead deer and the siding of houses rushed by. Helicopters circling overhead trying to rescue people clinging to the tops of trees, stranded in the middle of the river.

Davis said that even though she was just a kid, she remembers the helicopters and army trucks swarming the area. She even took a photo of one of the helicopters above with her Le Clic camera. Camp Capers was up a hill, she said, so the children there were able to shelter in place. But, she said, the mood was tense.

“We were told that 10 didn’t make it,” Davis said. “It just became very haunted and eerie. I wanted nothing to do with that river.”

The day was marked by a series of awful events. One 14-year-old girl in the Guadalupe grabbed a rope hanging from a helicopter but was unable to hang on long enough and fell to her death. Another girl caught in the river’s waves kept trying to grab a helicopter rope, but lost strength and was swept away. A teenager, John Bankston Jr, worked to save the younger kids when the camp bus stalled, carrying them on his back to dry land. He was in the river when the wall of water hit. Bankston was the only person whose body was never recovered.

Moore, the local reporter, said his TV station sent out a helicopter and they helped search for people. “We were flying up and down the river looking for survivors,” Moore said. “Later in the day, John Bankston Sr got in the helicopter and we flew him up and down the river for hours looking for his son.”

“I covered a lot of horrific stuff, from the Branch Davidians and earthquakes and hurricanes and Oklahoma City,” said Moore, who is now an author. “And this one has haunted me, just because of the kids.”

That year, the Texas water commission’s flood management unit made a dedication to the children who lost their lives in Comfort.

“When something like this occurs, we must all look into ourselves to see if we are doing all we can to prevent such a tragic loss of life,” read the dedication, written by Roy Sedwick, then state coordinator for the unit. Sedwick wrote that he was resolved to promote public awareness and flood warnings in Texas, “so that future generations will be safe from the ravages of flash floods”.

‘Are we doing enough to warn people?’

The National Weather Service’s storm report from the 1987 flood in Comfort paints more unsettling parallels with last week’s tragedy. Up to 11.5in (29cm) of rain fell near the small hamlet of Hunt that day, causing the river to surge 29ft. A massive flood wave emerged and travelled down the Guadalupe to Comfort.

During the recent floods in Kerr county, an estimated 12in of rain fell in a matter of hours during another heavy, slow-moving thunderstorm. This time, Hunt was the hardest hit, with the Guadalupe River again rising dozens of feet and setting a record-high crest of at least 37.5ft at its peak, according to the US Geological Survey. Many people along the river were given little to no warning.

The National Weather Service issued 22 alerts through the night and into the next day. But in the rural area, where cell service can be spotty, many residents said they didn’t get the alerts or they came too late, after the flash flood hit. No alerts were sent by Kerr county’s local government officials.

Other parts of Hill Country, such as in Comal county and on the Pedernales River, have siren systems. When high flood waters trigger the system, they blare “air raid” sirens giving notice to evacuate and get to high ground.

In Comfort, the 1987 tragedy still casts a shadow over the town. But on 4 July, the hamlet avoided much of the disaster that hit neighboring communities. Comfort recently worked to scrape together enough money to expand its own emergency warning system and installed sirens that are set off during floods. Over the last year, the volunteer fire department sounded the alarm every day at noon, so residents could learn to recognize the long flat tone.

So, when the raging Guadalupe waters once again rushed toward Comfort over the holiday weekend, sirens echoed throughout the town. This time, the volunteer fire department confirmed, all residents evacuated in time and there was no loss of life.

Kerr county, meanwhile, had been looking at installing a flood siren system for the past decade. But the plan got mired in political infighting and ultimately stalled when the county was presented with a $1m price tag. Earlier this year, state lawmakers introduced a house bill to fund early warning systems across Texas that could have included siren towers along the Guadalupe. And even though the bill overwhelmingly passed in the house, it died in the senate. In the aftermath of the 4 July catastrophe, the state says it will now fund such a system.

While it’s impossible to say whether such a warning system would have changed the outcome, given the massive expanse of Kerr county, experts say these types of weather events are going to keep happening and intensifying, so communities need to be prepared.

“This is a conversation for the entire country when it comes to areas that are prone to flash floods,” said the meteorologist Di Liberto. “Are we doing enough as a society to warn people?”

German (DE)

German (DE)  English (US)

English (US)  Spanish (ES)

Spanish (ES)  French (FR)

French (FR)  Hindi (IN)

Hindi (IN)  Italian (IT)

Italian (IT)  Russian (RU)

Russian (RU)  5 hours ago

5 hours ago

Comments